Ji (Chinese: 筓); pinyin: Jī) (also known asFazan(Chinese: 髮簪); pinyin: Fà zān),Zanzi or Zan (Chinese: 簪子or簪); pinyin: Zānzi or zān) for short)[1][2] and Chai(Chinese: 钗); pinyin: Chāi) are generic terms for hairpin in China.[3] 'Ji' (with the same character of 笄) is also the term used for hairpins of the Qin dynasty.[4] The earliest form of Chinese hair stick was found in the Neolithic Hemudu culture relics; the hair stick was called Ji (Chinese: 筓); pinyin: Jī), and were made from bones, horns, stones, and jade.[5]

Hairpins are an important symbol in Chinese culture,[1] and are associated with many Chinese cultural traditions and customs.[6] They were also used as every day hair ornaments in ancient China;[3] all Chinese women would wear a hairpin, regardless of their social rank.[7] The materials, elaborateness of the hairpin's ornaments, and the design used to make the hairpins were markers of the wearer's social status.[1][6] Hairpins could be made out of various materials, such as jade, gold, silver, ivory, bronze, bamboo, carved wood, tortoiseshell and bone, as well as others.[3][8][1][9]

Prior to the establishment of the Qing dynasty, both men and women coiled their hair into a bun using a ji.[3] There were many varieties of hairpin, many having their own names to denote specific styles, such as zan, ji, chai, buyao and tiaoxin.[10][3][11]

Cultural

Burials

During the Chinese funeral period, women in mourning were not allowed to wear hairpins.[1]

Ji ceremony

Ji played an important role in the coming-of age of Han Chinese women.[1][4] Before the age of 15 years old, women did not use hairpins, and always kept their hair in braids.[1] When a woman turned 15, she stopped wearing braids, and a hairpin ceremony called "Ji Li" (笄礼), or "hairpin initiation", would be held to mark the rite of passage.[3][1][6][4] During the ceremony, their hair would be coiled into a bun with a ji hairpin.[1][4] After the ceremony, the woman would be eligible for marriage.[3][6][4]

Hairpins as a love token

Betrothal and wedding customs

When engaged to be married, Chinese women would take the hairpin from their hair and give it to their male fiancé.[1] After the wedding, the husband would then return the hairpin to his newly-wed wife by placing it back in her hair.[1]

Separation and reunion love token

The chai hairpin[12] also used to be a form of love token; when lovers were forced to break apart, they would often break a hairpin in half, and each would keep half of the hairpin until they were reunited.[3]

Similarly, when married couples were separated for a long period of time, they would break a hairpin in two and each keep one part.[1] If they were to meet again in the future, they would then put the hairpin together again, as a proof of their identity and as a symbol of their reunion.[1]

Design and construction

Materials

Initially, Chinese people liked hairpins which were made out of bone and jade.[13] Hairpins which were made out of carved jade appeared in China as early as the Neolithic Period (c. 3000–1500 BC), along with jade carving technology.[7] Some ancient Chinese hairpins dating from the Shang dynasty can still be found in some museums.[14]

By the Bronze Age, hairpins which were made out of gold had been introduced into China by people living on the country's Northern borders.[13] Some ancient Chinese hairpins dating back to 300 BC were made from bone, horn, wood, and metal.[8]

The art of engraving wood first appeared in the Tang dynasty, and this new form of art was then applied to large wooden Chinese hairpins.[15] Many of these wooden hairpins were then coated with silver.[15]

In the Ming dynasty, the hairpins became more elaborate, and the carvings were made on silver, ivory, and jade, with pearl being used often as a setting.[15]

Decorations

Hairpins could also be decorated with gemstones, as well as designs of flowers, dragons, and phoenixes.[8]

Types

There are various types of Chinese hairpins:

Zan

The Zan is a type of hairpin with a single pin.[10][9] The Zan could also come in different styles such as:[10]

- Ji-style: A style of zan hairpin which likely refers to the hairpin used to secure the hair in a bun.[10]

- Ruyi-style: A style of zan hairpin in the shape of a ruyi scepter.[10]

- Tiger-head style[10]

- Round-dragon style[10]

-

Shang dynasty bone hairpin

-

Shang Bone Ji

-

Shang bronze hairpin

-

Shang dynasty jade hairpin

-

Spring & Autumn Bronze Hairpin

-

Warring States period bronze hairpin

-

Tang dynasty jade hairpin.

-

Coral hairpin, Song dynasty.

-

Hairpin from Southern Song.

-

Ming jade hairpin decorated with flowers.

-

Ming gold hairpins

-

Tomb of Prince Chuang of Liang-gold hairpins

-

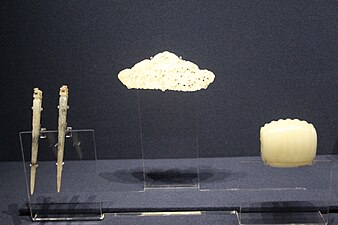

Ming dynasty Jade Hairpins & Ornaments

-

Ming dynasty Hairpins & Gold Earrings

-

Ming Gold Hairpins

-

Ming Gold Earrings and Hairpin

-

Ming Gold Hairpin and gourd earrings

-

Hairpin from China, Qing dynasty, nephrite,

-

Qing dynasty hairpin, Silver gilt

Phoenix hairpin

Phoenix (Fenghuang) hairpin originated in Qin dynasty and had an upper part made of gold and silver while the feet was made of tortoise shell; it later evolved into the fengguan during the Song dynasty. The fengguan then continued to evolve further in the Ming and Qing dynasties, and in the modern republic.[16] In the Han dynasty, an imperial edict decreed that the hairpin with fenghuang decorations had to become the formal headpiece for the empress dowager and the imperial grandmother.[16] The Fenghuang is an auspicious bird in Chinese tradition and is believed to represent the empress or the bride in a wedding.[17] Phoenix hairpins were also made and used by Peranakan women after settling in the Straits as part of their wedding headdresses.[17]

- Phoenix (Fenghuang) hairpin

-

A pair of fire-gilded silver phoenix hairpins of the Southern Song dynasty.

-

Ming-Qing Gold Earrings & phoenix Hairpin

-

Golden phoenix hairpins from the tomb of Prince Chuang of Liang, Ming dynasty, 15th century

Chai

The chai is a type of hairpin with double or multiple pins.[10][9] The double-pin chai evolved from the zan; it was frequently found in Chinese poetry and literature as it played an important symbol and as a love token.[12]

-

Jin dynasty (Western & Eastern) Silver Hairpin

-

Tang dynasty chai.

-

Ming dynasty gold hairpin

-

Yuan dynasty chai.

-

peony gold hairpin

-

Tang dynasty,silver,gilt - Royal Ontario Museum

-

Tang Gilded Silver Hairpins

-

Ming Gold Hairpin

-

Silver hairpin of Tang Dynasty

-

Liao dynasty Gold Hairpin

-

Tang Gilded Silver Hairpin

-

Ming dynasty gold chai

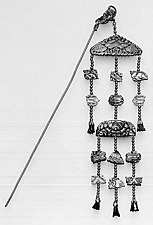

Buyao

The buyao was an elaborate and exquisite form of hairpin which denoted noble status.[3] It was generally made of gold and was often decorated with jewels (such as pearls and jade) and carved designs (such as in the shape of dragons or phoenix).[3][13] It looked similar to a zan,[12] but one of its main characteristics is its dangling features, which gave it its name 'buyao' (lit. "shake as you go" or "that sway with each step" or "step shake").[3][9][18][12] The buyao became popular in the Western Han dynasty.[13]

-

Qing dynasty gold phoenix zan hairpin.

-

Buyao, 18th century

Diancui hairpin

The diancui hairpin, also known as "kingfisher feather hairpin",[19] were made using the traditional Chinese art of diancui.[18]

-

Kingfisher feather hairpin.

-

Kingfisher feather hairpin

-

Tian-tsui cricket-shaped hairpin

Flower-hairpin headdresses

The Flower-hairpin headdresses is a generic term which was used to refer to the jewelry and headdresses worn by the Song dynasty Empresses and imperial concubines.[20] The Flower-hairpin headdresses were decorated with flower hairpins.[20] Different numbers of flowers were used depending on the imperial consorts' ranks and specific imperial rules were issued on their usage.[20]

Jin chan yu yue

Jin Chan yu yue (Chinese: 金蟬玉葉); pinyin: Jīn chán yù yè) Known as the "gold cicada on a jade leaf" hairpin, or "jin zhi yu ye" "Jin zhi yu yue" (Chinese: 金枝玉葉); pinyin: Jīnzhīyùyè) (lit. golden branches and jade leaves) a homonym for the Chinese idiom "one of noble birth",[21] a type of Ming dynasty hairpin in the shape of a cicada made of gold sitting on a piece of jade carved in the shape of a leaf.[9][21]

Tiaoxin

The Tiaoxin (Chinese: 挑心); pinyin: Tiāo xīn) is a Chinese hairpin worn by women in the Ming dynasty in their hair bun; the upper part of the hairpin was usually in the shape of a Buddhist statue, an immortal, a Sanskrit word, or a phoenix.[11] The Chinese character shou (寿, "longevity") could also be used to decorate the hairpin.[11][22]

See also

- Hairpin

- Hair stick

- List of Hanfu headwear

- Kanzashi - the Japanese equivalent

- Binyeo - the Korean equivalent

- Fengguan - phoenix crown

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Hairpins in Society and Art". Hairpin Museum 百鍊鋼化作繞髮柔 髮簪博物館. Retrieved 2021-05-05.

- ^ Wu, Shu-Ling (2019). Mastering advanced modern Chinese through the classics. Haiwang Yuan. Abingdon, Oxon: Taylor & Francis. pp. 125, 233. ISBN 978-1-315-20897-8. OCLC 1053623258.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Historical hair ornaments and their social connotations". usa.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 2021-05-05.

- ^ a b c d e Hidden dimensions of education : rhetoric, rituals and anthropology. Werler, Tobias. Wulf, Christoph. Waxmann. 2006. pp. 165–168. ISBN 3-8309-1739-2. OCLC 470776855.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "周原遗址出土的骨笄".

- ^ a b c d "Chinese cloisonne hairpin". collection.maas.museum. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- ^ a b "Material & Technology". Hairpin Museum 百鍊鋼化作繞髮柔 髮簪博物館. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- ^ a b c Sherrow, Victoria (2006). Encyclopedia of hair : a cultural history. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 179. ISBN 0-313-33145-6. OCLC 61169697.

- ^ a b c d e Yuan, Xiaowei (2017). "Traditional Chinese Jewelry Art: Loss, Rediscovery and Reconstruction Take Headwear as an Example". Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Humanities (ICCESSH 2017). Atlantis Press. pp. 550–554. doi:10.2991/iccessh-17.2017.135. ISBN 978-94-6252-351-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Living the good life : consumption in the Qing and Ottoman empires of the eighteenth century. Elif Akçetin, Suraiya Faroqhi. Leiden: Brill. 2018. p. 205. ISBN 978-90-04-35345-9. OCLC 1008768840.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c "Golden Hairpin Decorated with Character "Shou" - Chengdu Museum". www.cdmuseum.com. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- ^ a b c d "Tradition of China - Hair Ornament Culture | ChinaFetching". ChinaFetching.com. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- ^ a b c d "Hair Accessories - MIHO MUSEUM". www.miho.jp. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- ^ "Hairpin 13th–11th century B.C. China". www.metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 2021-05-06. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- ^ a b c Lester, Katherine Morris (2004). Accessories of dress : an illustrated encyclopedia. Bess Viola Oerke, Helen Westermann. Mineola, New York. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-486-14049-0. OCLC 857715305.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Cheng, Hui-Mei (2001). "Research on the Form and Symbolism of the Chinese Wedding Phoenix Crown". Proceedings of the Korea Society of Costume Conference: 59–61.

- ^ a b "Phoenix hairpin". www.roots.gov.sg. Retrieved 2022-10-22.

- ^ a b Wu, Yiqian (2020). A Study of Historical Transformation and Cultural Change in Chinese Dian-cui Jewellery [Thesis]. University of Sydney (Thesis). pp. 21, 30, 33, 43–44. hdl:2123/24005.

- ^ "Kingfisher feather hairpin from China". collection.maas.museum. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- ^ a b c Zhu, Ruixi; 朱瑞熙 (2016). A social history of middle-period China : the Song, Liao, Western Xia and Jin dynasties. Bangwei Zhang, Fusheng Liu, Chongbang Cai, Zengyu Wang, Peter Ditmanson, Bang Qian Zhu (Updated ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-1-107-16786-5. OCLC 953576345.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Liu, Fang (2011). "Rare collections of the Ming and Qing Dynasties". europe.chinadaily.com.cn. Archived from the original on 2021-05-06. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- ^ "Traditional Chinese Hair Jewelry - Ming Style Diji & Tiaopai". www.newhanfu.com. 2020-12-04. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

Recent Comments