The Kachin Hills are a heavily forested group of highlands in the extreme northeastern area of the Kachin State of Burma. They consist of a series of ranges running mostly in a N/S direction, including the Kumon Bum subrange of which the highest peak is Bumhpa Bum with an elevation of 3,411 metres (11,191 ft)[1] one of the ultra-prominent peaks of Southeast Asia. The Kachin Hills are inhabited by the Kachin people.

Geography

The country within the Kachin Hill tracts is roughly estimated at 19,177 square miles (49,670 km2), and consists of a series of ranges, for the most part running north and south, and intersected by valleys, all leading towards the Irrawaddy River, which drains the whole country.[2]

British administration

According to the Kachin Hill Tribes Regulation of 1895, administrative responsibility was accepted by the British government on the left bank of the Irrawaddy for the country south of the Nmaikha, and on the right bank for the country south of a line drawn from the confluence of the Malikha and Nmaikha through the northern limit of the Laban district and including the jade mines. The tribes north of this line were told that if they abstained from raiding to the south of it they would not be interfered with. South of that line peace was to be enforced and a small tribute taken, with a minimum of interference in their private affairs.[2]

On the British side of the border, the chief objects of Britain's colonial policy were the disarmament of the tribes and construction of frontier and internal roads. A small tribute was taken by the British. The Kachins were subject to many British "police operations" and two fighting expeditions:[2]

British incursion of 1892-93

The city of Bhamo was occupied by the British on December 28, 1885, and almost immediately, trouble began. Constant punitive measures were carried out by the military police; but in December 1892, a police column proceeding to establish a post at Sima was heavily attacked, and simultaneously the town of Myitkyina was raided by Kachin fighters. A force of 1,200 troops was sent to put down the rebellion. The Kachin fighters received their final blow at Palap, but not before three British officers were killed, three wounded and 102 sepoys and followers killed and wounded.[2][undue weight? ]

British incursion of 1895-96

The continued "misconduct" of the Sana Kachins from beyond the administrative border rendered punitive measures necessary, in the eyes of British colonists. No retaliation had taken place since the attack on Myitkyina in December 1892. Now two columns were sent up, one of 250 rifles from Myitkyina, the other of 200 rifles from Mogaung, marching in December 1895. The resistance was insignificant, and the fighting resulted in a complete victory for the British. A strong force of military police was stationed at Myitkyina, with several outposts in the Kachin hills.[2]

Pianma Incident

In 1910, during the very last year of Qing Empire, the British occupied Hpimaw[3] (Pianma)[4] in the Pianma Incident, as well as a part of what is now Northern Kachin state in 1926-27 and part of the Wa states in 1940.[5][6]

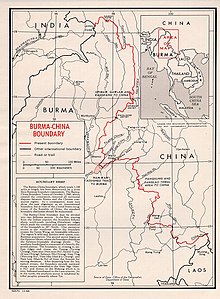

Independent Burma

Myanmar relinquished[3][7] the eastern villages of Hpimaw (Pianma) and adjacent Gawlam (Gulang)[8] and Kangfang (Gangfang)[9] to the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1960, ending the political boundary dispute. Although Kachin Hills had been granted much autonomy under the 1947 constitution, the Myanmar government has since integrated it into the rest of the country, but not without the resistance of groups such as the Kachin Independence Organisation, which has fought the government since 1961.[10]

See also

References

- ^ "Bumhpa Bum - Peakbagger.com". www.peakbagger.com.

- ^ a b c d e One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Kachin Hills". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 626.

- ^ a b "International Boundary Study No. 42 – Burma-China Boundary" (PDF). US DOS. 30 November 1964. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ "Lúshuǐ Xiàn Piànmǎ Zhèn Piànmǎ Cūnwěihuì Xiàpiànmǎ Cūn" 泸水县片马镇片马村委会下片马村 [Xiapianma Village, Pianma Village Committee, Pianma Town, Lushui County]. ynszxc.gov.cn (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2015-04-02.

- ^ Gillogly, Kathleen (2006). "Transformations of Lisu Social Structure Under Opium Control and Watershed Conservation in Northern Thailand" (PDF). evols.library.manoa.hawaii.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2020-09-13.

- ^ "Yunnan | province, China". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2023-10-30.

In 1910 the British, then established in Burma, induced the tusi of Pianma (Hpimau) to defect from the central Chinese government, and they then occupied his territory in northwestern Yunnan. Britain also forced China to give up a tract of territory in what is now the Kachin state of Myanmar (1926–27), as well as the territory in the Wa states (1940).

- ^ "International Boundary Study No. 42 – Burma-China Boundary" (PDF). USDOS. 30 November 1964. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

Agreement on the Question of the Boundary signed on January 28, 1960...(b) the villages of Hpimaw, Gawlum, and Kangfang would be Chinese;...(d) the Panhung-Panlao tribal area would be exchanged (for Namwan); and (e) with the exception of d, the 1941 boundary in the Wa states would be accepted...

- ^ "Lúshuǐ Xiàn Piànmǎ Zhèn Gǔlàng Cūnwěihuì" 泸水县片马镇古浪村委会 [Gulang Village Committee, Pianma Town, Lushui County]. ynszxc.gov.cn (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2015-04-03.

- ^ "Lúshuǐ Xiàn Piànmǎ Zhèn Gǎngfáng Cūnwěihuì" 泸水县片马镇岗房村委会 [Gangfang Village Committee, Pianma Town, Lushui County]. ynszxc.gov.cn (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2015-04-02.

- ^ Fuller, Thomas (11 May 2009), "Ethnic Groups in Myanmar Hope for Peace, but Gird for Fight", The New York Times, archived from the original on 30 Jan 2013

Recent Comments