The Edenton Tea Party was a political protest in Edenton, North Carolina, in response to the Tea Act, passed by the British Parliament in 1773.

In October 1774, 51 women from Edenton and the surrounding area signed a statement dated October 25, 1774 affirming their support for the first North Carolina Provincial Congress' decision to boycott of British goods to protest the Crown's mistreatment of the American Colonies.[1] The boycott was one of the events that led up to the American Revolution (1775–1781).[2]

The 51 Signers' statement, known as the "Edenton Resolves", forms one of the earliest-known protests written and organized by women in the American Colonies, and this protest later became known as the "Edenton Tea Party".[3]

Background

The British had implemented taxes and policies against Colonial Americans[4] to offset the money spent by the British during the French and Indian Wars (1754–1763).[5] They also taxed the square footage of colonist's homes, but they did not represent the colonists in the British Parliament.[6] When the Tea Act of 1773 was passed by the Parliament, colonists became especially angry. The act gave the British East India Company a monopoly in the colonies.[4] Tea was important to colonists for a couple of reasons. Drinking tea was safer than drinking water, although they did not know at that time that it destroyed germs in the water. It was also a sign of sophistication and luxury.[6] In addition, it was a long-standing daily tradition of the British, and colonial social events "were defined by the amount and quality of tea provided".[7]

The money that the British gathered from the colonists was to be used to make judges and governors loyal to the British and prove that the British led the thirteen colonies.[6]

The First Continental Congress passed non-importation resolutions in 1774 to boycott British teas and textiles.[4] At that time, the ideal woman was "fragile, fair, not particularly bright, and certainly not interested in public affairs".[8] It was expected that woman would marry and have children, and thus focus on their roles as wives and mothers over sometimes short lives, and to the exclusion of being involved in political issues. By the 18th century, many women were able to read newspapers, which were published more in a more widespread than earlier. Through the newspapers, women learned about political affairs.[9]

Since women would be required to find substitutes for British tea, cloth, and other taxed goods, it was crucial to have their support during the boycotts and protests organized and popularized by men.[8] Colonial women boycotted all British imports and even formed groups and signed resolutions, like the Edenton Tea Party, to encourage other women to protest against taxes without representation. Unlike the men of the Boston Tea Party, the women did not hide their identities.[6][10] There were similar tea parties in other ports. Protesting and boycotting allowed women opportunities to act as patriots, standing with men on this political issue.[10] Historian Carol Berkin states,

Women and girls were partners with their husbands, fathers, brothers, and sons in the public demonstrations against the new British policies and, if they were absent from the halls of the colonial legislatures, their presence was crucial in the most effective protest strategy of all: the boycott of British manufactured goods.[11]

The succession of taxes and policies against the colonists led to the Revolutionary War (1775–1781).[8][12]

Edenton, listed on ship's papers as "The port of Roanoke", was an international port for the transit of goods between the Colony of North Carolina, Europe, and the West Indies. Two-masted schooners had left the port with tobacco, corn, salt fish, lumber, and turpentine.[13]

Edenton Tea Party

In October 1774, 51 ladies from Edenton and the surrounding area signed a statement, dated October 25, 1774, supporting the resolutions passed by the first North Carolina Provincial Congress in the previous August.[14] The Provincial Congress' resolutions were passed to protest the British Tea Act of 1773.[2][15][a][b]

The "Edenton Resolves" affirmed,

Edenton, North Carolina, Oct. 25, 1774. As we cannot be indifferent on any occasion that appears nearly to affect the peace and happiness of our country, and as it has thought necessary, for the public good, to enter into several particular resolves by a meeting of Members deputed from the whole Province, it is a duty which we owe, not only to our near and dear connections who have concurred in them, but to ourselves who are essentially interested in their welfare, to do every thing as far as lies in our power to testify our sincere adherence to the same; and we do therefore accordingly subscribe this paper, as a witness of our fixed intention and solemn determination to do so.[19]

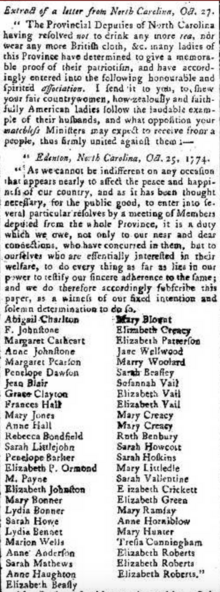

This statement was signed by the 51 women: Abigail Charlton, F. Johnstone, Margaret Cathcart, Anne Johnstone, Margaret Pearson, Penelope Dawson, Jean Blair, Grace Clayton, Frances Hall, Mary Jones, Anne Hall, Rebecca Bondfield, Sarah Littlejohn, Penelope Barker, Elizabeth P. Ormond, M. Payne, Elizabeth Johnston, Mary Bonner, Lydia Bonner, Sarah Howe, Lydia Bennet, Marion Wells, Anne Anderson, Sarah Mathews, Anne Haughton, Elizabeth Beasley, Mary Blount, Elizabeth Creacy, Elizabeth Patterson, Jane Wellwood, Mary Woolard, Sarah Beasley, Susannah Vail, Elizabeth Vail, Elizabeth Vail, Mary Creacy, Mary Creacy, Ruth Benbury, Sarah Howcutt, Sarah Hoskins, Mary Littledle, Sarah Valentine, Elizabeth Crickett, Elizabeth Green, Mary Ramsey, Anne Horniblow, Mary Hunter, Tresia Cunningham, Elizabeth Roberts, Elizabeth Roberts, Elizabeth Roberts.[21]

The Edenton Resolves first appeared in the Postscript to the November 3, 1774 edition of the Virginia Gazette and then in the London newspapers throughout the following January.[22]

An extract of a letter containing a copy of the Resolves sent to a recipient in Britain was also published in the London newspapers ahead of the October 25, 1774 statement and list of signatures. The letter extract, dated October 27th, states,

Extract of a letter from North Carolina, Oct. 27. The Provincial Deputies of North Carolina having resolved not to drink any more tea, nor wear any more British cloth, &c. many ladies of this Province have determined to give a memorable proof of their patriotism, and have accordingly entered into the following honourable and spirited association. I send it to you, to shew your fair countrywomen, how zealously and faithfully American ladies follow the laudable example of their husbands, and what opposition your matchless Ministers may expect to receive from a people thus firmly united against them.[23]

The identities of the letter's author and recipient are unknown, as is the original author of the "Edenton Resolves".

Aftermath

As female voices were not always welcome in politics in eighteenth-century British society, the reaction in England was mostly derogatory and dismissive, as seen in the satirical print, "A Society of Patriotic Ladies, at Edenton in North Carolina", published on March 25, 1775 by printers R. Sayer & J. Bennett, and attributed to engraver Phillip Dawe.[25] London resident Arthur Iredell also mocks the 51 Signers' action in a letter to his brother, James (an Edenton resident), when he claims,

The Edenton ladies, conscious, I suppose, of this superiority on their side, by former experience, are willing, I imagine, to crush us into atoms, by their omnipotency; the only security on our side, to prevent the impending ruin, that I can perceive, is the probability that there are but few places in America which possess so much female artillery as Edenton...[26]

Despite the threat of ridicule from across the Atlantic, women who participated in protests against taxation without representation were often praised as patriots by the Colonial American press.[4] After the "Edenton Resolves" were published, other women followed suit by swearing off tea.[27] Southern women danced in ballgowns made from homespun fabric (that started with the homespun movement). Northern women had spinning bees for the production of homemade material.[28] A ship-load of imported East India Company tea was locked away in a port in Charles Town (now Charleston, South Carolina) for months because it could not be sold with the tax.[27] At the start of the Revolution,[29] a group of patriots captured the tea and sold it to other patriots to fund the rebellion against the British.[27] They had also ousted royal officials and agents at the time.[27] The Daughters of Liberty, like the Sons of Liberty, boycotted British goods.[30]

There was little written about the Edenton Tea Party for some time. The first book written about the event was The Historic Tea Party of Edenton, 1774: Incident in North Carolina Connected with Taxation written by Richard Dillard in 1892. In 1907, Mary Dawes Staples wrote an article entitled The Edenton Tea Party, which was published by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR).[31] Some of the publications produced in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries contain additional details about the Edenton Tea Party that cannot be verified against eighteenth century primary sources.

Maggie Mitchell, in 2015, performs an extensive review of the events of the Edenton Tea Party in "Chapter Three: Uncovering the Events of October 24, 1776" in Treasonous Tea: The Edenton Tea Party of 1774.[32]

In 1908, a plaque was dedicated by the Daughters of the American Revolution of North Carolina and placed in the state Capitol Building in Raleigh, North Carolina. It honored her leadership at the Edenton Tea Party.[33] In 1940, a marker was placed at West Queen Street (US 17 Business) in Edenton by the North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program. It states, "Women in this town led by Penelope Barker in 1774 resolved to boycott British imports. Early and influential activism by women."[17]

See also

- Boston Tea Party

- Philadelphia Tea Party

- Continental Association adopted on October 20, 1774

Notes

- ^ Mitchell states that although it is widely stated that the meeting took place at the home of Elizabeth King, there is little actual evidence that this occurred.[16] In addition, her house may have been too small for such a gathering.[17]

- ^ The signers of the declaration include Abagail Charlton, Mary Blount, F. Johnstone, Elizabeth Creacy, Margaret Cathcart, Elizabeth Patterson, Anne Johnstone, Jane Wellwood, Margaret Pearson, Mary Woolard, Penelope Dawson, Sarah Beasley, Jean Blair, Susannah Vail, Grace Clayton, Elizabeth Vail, Frances Hall, Mary Jones, Mary Creacy, Anne Hall, Rebecca Bondfield, Ruth Benbury, Sarah Littlejohn, Sarah Howcott, Penelope Barker, Sarah Hoskins, Elizabeth P. Ormond, Mary Littledle, M. Payne, Sarah Valentine, Elizabeth Johnston, Elizabeth Crickett, Mary Bonner, Elizabeth Green, Lydia Bonner, Mary Ramsay, Sarah Howe, Anne Horniblow, Lydia Bennet, Mary Hunter, Marion Wells, Tresia Cunningham, Anne Anderson, Elizabeth Roberts, Sarah Mathews, Anne Haughton, and Elizabeth Beasly.[18]

References

- ^ "NCpedia | NCpedia". www.ncpedia.org. Retrieved 2024-05-22.

- ^ a b Howat, Kenna (2017), Mythbusting the Founding Mothers, National Women's History Museum

- ^ "Edenton Tea Party Overview" (PDF). Edenton Historical Commission.

- ^ a b c d Michaels, Debra. "Penelope Barker (1728–1796)". National Women's History Museum. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ^ Mitchell 2015, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b c d Silcox-Jarrett 2000, p. 17.

- ^ Mitchell 2015, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Collins 2003, p. 78.

- ^ Mitchell 2015, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b Mitchell 2015, p. 7.

- ^ Mitchell 2015, p. 37.

- ^ Silcox-Jarrett 2000, p. 16.

- ^ Garrison 1993, pp. 76–77.

- ^ "NCpedia | NCpedia". www.ncpedia.org. Retrieved 2024-05-22.

- ^ Martin, Michael G. Jr. (December 2021). "Barker, Penelope". NCpedia. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- ^ Mitchell 2015, p. 16.

- ^ a b "Marker: A-22 Edenton Tea Party". www.ncmarkers.com. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

- ^ "Edenton, North Carolina, October 25, 1774". The Virginia Gazette. pp. November 3, 1774.

- ^ "Virginia Gazette: Purdie and Dixon, Nov. 03, 1774, pg. 1 | The Colonial Williamsburg Official History & Citizenship Site". research.colonialwilliamsburg.org. Retrieved 2024-05-22.

- ^ "Morning Chronicle And London Advertiser Archives, Jan 16, 1775, p. 2". NewspaperArchive.com. 1775-01-16. Retrieved 2024-05-22.

- ^ "Virginia Gazette: Purdie and Dixon, Nov. 03, 1774, pg. 1 | The Colonial Williamsburg Official History & Citizenship Site". research.colonialwilliamsburg.org. Retrieved 2024-05-22.

- ^ "Virginia Gazette: Purdie and Dixon, Nov. 03, 1774, pg. 1 | The Colonial Williamsburg Official History & Citizenship Site". research.colonialwilliamsburg.org. Retrieved 2024-05-22.

- ^ "Morning Chronicle And London Advertiser Archives, Jan 16, 1775, p. 2". NewspaperArchive.com. 1775-01-16. Retrieved 2024-05-22.

- ^ "A society of patriotic ladies, at Edenton in North Carolina". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2024-05-22.

- ^ "A society of patriotic ladies, at Edenton in North Carolina". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2024-05-22.

- ^ McRee, Griffith John (1857). Life and Correspondence of James Iredell: One of the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States. United States: D. Appleton. pp. 230–231.

- ^ a b c d Garrison 1993, p. 77.

- ^ Collins 2003, p. 79.

- ^ Garrison, Webb (1988). A treasury of Carolina tales. Nashville, Tenn. : Rutledge Hill Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-934395-75-5.

- ^ Mitchell 2015, p. 8.

- ^ Mitchell 2015, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Mitchell 2015, pp. 39–49.

- ^ Waldrup 2004, p. 119.

Sources

- Collins, Gail (2003). "What have I to do with politicks". America's Women: Four Hundred Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-06-018510-7.

- Garrison, Webb (1993). "First Women's Movement Urged Cider, Buttermilk, and Water". Great stories of the american revolution. Rutledge Hill Press. ISBN 978-1-55853-270-0.

- Mitchell, Maggie. Treasonous Tea: The Edenton Tea Party of 1774 (Masters). Liberty University. that was a Master's dissertation, and published Mitchell, Maggie (2015). Treasonous Tea: The Edenton Tea Party of 1774. Liberty University.

- Silcox-Jarrett, Diane (2000). "Penelope Barker, Leader of the Edenton Tea Party'". Heroines of the American Revolution: America's founding mothers. New York : Scholastic Inc. ISBN 978-0-439-25947-7.

- Waldrup, Carole Chandler (2004). More Colonial women: 25 pioneers of early America. Jefferson, N.C. : McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0-7864-1839-8.

Recent Comments