Alexander III of Macedon (20/21 July 356 – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great (Greek: Μέγας Ἀλέξανδρος, Mégas Aléxandros), was a king of Macedon or Macedonia ([Βασιλεύς Μακεδόνων] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help)), a state in the north eastern region of Greece, and by the age of thirty was the creator of one of the largest empires in ancient history, stretching from the Ionian sea to the Himalaya. He was undefeated in battle and is considered one of the most successful commanders of all time.[1] Born in Pella in 356 BC, Alexander was tutored by the famed philosopher Aristotle. In 336 BC he succeeded his father Philip II of Macedon to the throne after he was assassinated. Philip had brought most of the city-states of mainland Greece under Macedonian hegemony, using both military and diplomatic means.

Upon Philip's death, Alexander inherited a strong kingdom and an experienced army. He succeeded in being awarded the generalship of Greece and, with his authority firmly established, launched the military plans for expansion left by his father. In 334 BC he invaded Persian-ruled Asia Minor and began a series of campaigns lasting ten years. Alexander broke the power of Persia in a series of decisive battles, most notably the battles of Issus and Gaugamela. Subsequently he overthrew the Persian king Darius III and conquered the entirety of the Persian Empire.[i] The Macedonian Empire now stretched from the Adriatic sea to the Indus River.

Following his desire to reach the "ends of the world and the Great Outer Sea", he invaded India in 326 BC, but was eventually forced to turn back by the near-mutiny of his troops. Alexander died in Babylon in 323 BC, without realizing a series of planned campaigns that would have begun with an invasion of Arabia. In the years following Alexander's death a series of civil wars tore his empire apart which resulted in the formation of a number of states ruled by the Diadochi - Alexander's surviving generals. Although he is mostly remembered for his vast conquests, Alexander's lasting legacy was not his reign, but the cultural diffusion his conquests engendered.

Alexander's settlement of Greek colonists and culture in the east resulted in a new Hellenistic culture, aspects of which were still evident in the traditions of the Byzantine Empire until the mid-15th century. Alexander became legendary as a classical hero in the mold of Achilles, and features prominently in the history and myth of Greek and non-Greek cultures. He became the measure against which generals, even to this day, compare themselves and military academies throughout the world still teach his tactical exploits.[1] [ii]

Early life

Lineage and childhood

Alexander was born on 20 (or 21) July 356 BC,[2][3] in Pella, the capital of the Kingdom of Macedon. He was the son of Philip II, the King of Macedon. His mother was Philip's fourth wife Olympias, the daughter of Neoptolemus I, the king of Epirus.[4][5][6][7] Although Philip had either seven or eight wives, Olympias was his principal wife for a time.

As a member of the Argead dynasty, Alexander claimed patrilineal descent from Heracles through Caranus of Macedon.[iv] From his mother's side and the Aeacids, he claimed descent from Neoptolemus, son of Achilles;[v] Alexander was a second cousin of the celebrated general Pyrrhus of Epirus, who was ranked by Hannibal as, depending on the source, either the best[8] or second-best (after Alexander)[9] commander the world had ever seen.

According to the ancient Greek biographer Plutarch, Olympias, on the eve of the consummation of her marriage to Philip, dreamed that her womb was struck by a thunder bolt, causing a flame that spread "far and wide" before dying away. Some time after the wedding, Philip was said to have seen himself, in a dream, sealing up his wife's womb with a seal upon which was engraved the image of a lion.[4] Plutarch offers a variety of interpretations of these dreams: that Olympia was pregnant before her marriage, indicated by the sealing of her womb; or that Alexander's father was Zeus. Ancient commentators were divided as to whether the ambitious Olympias promulgated the story of Alexander's divine parentage, some claiming she told Alexander, others that she dismissed the suggestion as impious.[4]

On the day that Alexander was born, Philip was preparing himself for his siege on the city of Potidea on the peninsula of Chalcidike. On the same day, Philip received news that his general Parmenion had defeated the combined Illyrian and Paeonian armies, and that his horses had won at the Olympic Games. It was also said that on this day, the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus—one of the Seven Wonders of the World—burnt down, leading Hegesias of Magnesia to say that it burnt down because Artemis was attending the birth of Alexander.[2][6][10]

In his early years, Alexander was raised by his nurse, Lanike, the sister of Alexander's future friend and general Cleitus the Black. Later on in his childhood, Alexander was tutored by the strict Leonidas, a relative of his mother, and by Lysimachus.[11][12]

When Alexander was ten years old, a horse trader from Thessaly brought Philip a horse, which he offered to sell for thirteen talents. The horse refused to be mounted by anyone, and Philip ordered it to be taken away. Alexander, however, detected the horse's fear of his own shadow and asked for a turn to tame the horse, which he eventually managed. According to Plutarch, Philip, overjoyed at this display of courage and ambition, kissed him tearfully, declaring: "My boy, you must find a kingdom big enough for your ambitions. Macedon is too small for you", and bought the horse for him.[13] Alexander would name the horse Bucephalus, meaning "ox-head". Bucephalus would be Alexander's companion throughout his journeys as far as India. When Bucephalus died (due to old age, according to Plutarch, for he was already thirty), Alexander named a city after him (Bucephala).[14][15][16]

Adolescence and education

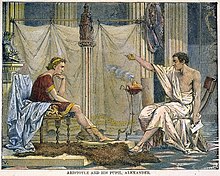

When Alexander was thirteen years old, Philip decided that Alexander needed a higher education, and he began to search for a tutor. Many people were passed over including Isocrates and Speusippus, the latter of whom was Plato's successor at the Academy and who offered to resign to take up the post. In the end, Philip offered the job to Aristotle, who accepted, and Philip gave them the Temple of the Nymphs at Mieza as their classroom. In return for teaching Alexander, Philip agreed to rebuild Aristotle's hometown of Stageira, which Philip had razed, and to repopulate it by buying and freeing the ex-citizens who were slaves, or pardoning those who were in exile.[17][18][19][20]

Mieza was like a boarding school for Alexander and the children of Macedonian nobles, such as Ptolemy, Hephaistion, and Cassander. Many of the pupils who learned by Alexander's side would become his friends and future generals, and are often referred to as the 'Companions'. At Mieza, Aristotle educated Alexander and his companions in medicine, philosophy, morals, religion, logic, and art. From Aristotle's teaching, Alexander developed a passion for the works of Homer, and in particular the Iliad; Aristotle gave him an annotated copy, which Alexander was to take on his campaigns.[21][22][23][24]

Philip's heir

Regency and ascent of Macedon

When Alexander became sixteen years old, his tutorship under Aristotle came to an end. Philip, the king, departed to wage war against Byzantium, and Alexander was left in charge as regent of the kingdom. During Philip's absence, the Thracian Maedi revolted against Macedonian rule. Alexander responded quickly; he crushed the Maedi insurgence, driving them from their territory, colonised it with Greeks, and founded a city named Alexandropolis.[25][26][27][28]

After Philip's return from Byzantium, he dispatched Alexander with a small force to subdue certain revolts in southern Thrace. During another campaign against the Greek city of Perinthus, Alexander is reported to have saved his father's life. Meanwhile, the city of Amphissa began to work lands that were sacred to Apollo near Delphi, a sacrilege that gave Philip the opportunity to further intervene in the affairs of Greece. Still occupied in Thrace, Philip ordered Alexander to begin mustering an army for a campaign in Greece. Concerned with the possibility of other Greek states intervening, Alexander made it look as if he was preparing to attack Illyria instead. During this turmoil, the Illyrians took the opportunity to invade Macedonia, but Alexander repelled the invaders.[29]

Philip joined Alexander with his army in 338 BC, and they marched south through Thermopylae, which they took after stubborn resistance from its Theban garrison. They went on to occupy the city of Elatea, a few days march from both Athens and Thebes. Meanwhile, the Athenians, led by Demosthenes, voted to seek an alliance with Thebes in the war against Macedonia. Both Athens and Philip sent embassies to try to win Thebes's favour, with the Athenians eventually succeeding.[30][31][32] Philip marched on Amphissa (theoretically acting on the request of the Amphicytonic League), captured the mercenaries sent there by Demosthenes, and accepted the city's surrender. Philip then returned to Elatea and sent a final offer of peace to Athens and Thebes, which was rejected.[33][34][35]

As Philip marched south, he was blocked near Chaeronea, Boeotia by the forces of Athens and Thebes. During the ensuing Battle of Chaeronea, Philip commanded the right, and Alexander the left wing, accompanied by a group of Philip's trusted generals. According to the ancient sources, the two sides fought bitterly for a long time. Philip deliberately commanded the troops on his right wing to backstep, counting on the untested Athenian hoplites to follow, thus breaking their line. On the left, Alexander was the first to break into the Theban lines, followed by Philip's generals. Having achieved a breach in the enemy's cohesion, Philip ordered his troops to press forward and quickly routed his enemy. With the rout of the Athenians, the Thebans were left to fight alone; surrounded by the victorious enemy, they were crushed.[36]

After the victory at Chaeronea, Philip and Alexander marched unopposed into the Peloponnese welcomed by all cities; however, when they reached Sparta, they were refused, and they simply left.[37] At Corinth, Philip established a "Hellenic Alliance" (modeled on the old anti-Persian alliance of the Greco-Persian Wars), with the exception of Sparta. Philip was then named Hegemon (often translated as 'Supreme Commander') of this league (known by modern historians as the League of Corinth). He then announced his plans for a war of revenge against the Persian Empire, which he would command.[38][39]

Exile and return

"At the wedding of Cleopatra, whom Philip fell in love with and married, she being much too young for him, her uncle Attalus in his drink desired the Macedonians would implore the gods to give them a lawful successor to the kingdom by his niece. This so irritated Alexander, that throwing one of the cups at his head, "You villain," said he, "what, am I then a bastard?" Then Philip, taking Attalus's part, rose up and would have run his son through; but by good fortune for them both, either his over-hasty rage, or the wine he had drunk, made his foot slip, so that he fell down on the floor. At which Alexander reproachfully insulted over him: "See there," said he, "the man who makes preparations to pass out of Europe into Asia, overturned in passing from one seat to another."

— Plutarch, describing the feud at Philip's wedding.[25]

After returning to Pella, Philip fell in love with and married Cleopatra Eurydice, the niece of one of his generals, Attalus. This marriage made Alexander's position as heir to the throne less secure, since if Cleopatra Eurydice bore Philip a son, there would be a fully Macedonian heir, while Alexander was only half Macedonian.[40] During the wedding banquet, a drunken Attalus made a speech praying to the gods that the union would produce a legitimate heir to the Macedonian throne. Alexander shouted to Attalus, "What am I then, a bastard?" and he threw his goblet at him. Philip, who was also drunk, drew his sword and advanced towards Alexander before collapsing, leading Alexander to say, "See there, the man who makes preparations to pass out of Europe into Asia, overturned in passing from one seat to another."[25]

Alexander fled from Macedon taking his mother with him, whom he dropped off with her brother in Dodona, capital of Epirus. He carried on to Illyria, where he sought refuge with the Illyrian King and was treated as a guest by the Illyrians, despite having defeated them in battle a few years before. Alexander returned to Macedon after six months in exile due to the efforts of a family friend, Demaratus the Corinthian, who mediated between the two parties.[25][41][42]

The following year, the Persian satrap (governor) of Caria, Pixodarus, offered the hand of his eldest daughter to Alexander's half-brother, Philip Arrhidaeus. Olympias and several of Alexander's friends suggested to Alexander that this move showed that Philip intended to make Arrhidaeus his heir. Alexander reacted by sending an actor, Thessalus of Corinth, to tell Pixodarus that he should not offer his daughter's hand to an illegitimate son, but instead to Alexander. When Philip heard of this, he scolded Alexander for wishing to marry the daughter of a Carian. Philip had four of Alexander's friends, Harpalus, Nearchus, Ptolemy and Erigyius exiled, and had the Corinthians bring Thessalus to him in chains.[40][43][44]

King of Macedon

Accession

In 336 BC, whilst at Aegae, attending the wedding of his daughter by Olympias, Cleopatra, to Olympias's brother, Alexander I of Epirus, Philip was assassinated by the captain of his bodyguard, Pausanias.[vi] As Pausanias tried to escape, he tripped over a vine and was killed by his pursuers, including two of Alexander's companions, Perdiccas and Leonnatus. Alexander was proclaimed king by the Macedonian army and by the Macedonian noblemen at the age of 20.[45][46][47]

Power consolidation

Alexander began his reign by eliminating any potential rivals to the throne. He had his cousin, the former Amyntas IV, executed, as well as having two Macedonian princes from the region of Lyncestis killed, while a third, Alexander Lyncestes, was spared. Olympias had Cleopatra Eurydice and her daughter by Philip, Europa, burned alive. When Alexander found out about this, he was furious with his mother. Alexander also ordered the murder of Attalus, who was in command of the advance guard of the army in Asia Minor. Attalus was at the time in correspondence with Demosthenes, regarding the possibility of defecting to Athens. Regardless of whether Attalus actually intended to defect, he had already severely insulted Alexander, and having just had Attalus's daughter and grandchildren murdered, Alexander probably felt Attalus was too dangerous to leave alive.[48] Alexander spared the life of Arrhidaeus, who was by all accounts mentally disabled, possibly as a result of poisoning by Olympias.[45][49][50][51]

News of Philip's death roused many states into revolt, including Thebes, Athens, Thessaly, and the Thracian tribes to the north of Macedon. When news of the revolts in Greece reached Alexander, he responded quickly. Though his advisors advised him to use diplomacy, Alexander mustered the Macedonian cavalry of 3,000 men and rode south towards Thessaly, Macedon's neighbor to the south. When he found the Thessalian army occupying the pass between Mount Olympus and Mount Ossa, he had the men ride over Mount Ossa. When the Thessalians awoke the next day, they found Alexander in their rear, and promptly surrendered, adding their cavalry to Alexander's force, as he rode down towards the Peloponnesus.[52][53][54][55]

Alexander stopped at Thermopylae, where he was recognized as the leader of the Amphictyonic League before heading south to Corinth. Athens sued for peace and Alexander received the envoy and pardoned anyone involved with the uprising. At Corinth, where occurred the famous encounter with Diogenes the Cynic, who asked him to stand a little aside as he was blocking the sun,[56] Alexander was given the title Hegemon, and like Philip, appointed commander of the forthcoming war against Persia. While at Corinth, he heard the news of the Thracian rising to the north.[53][57]

Balkan campaign

Before crossing to Asia, Alexander wanted to safeguard his northern borders; and, in the spring of 335 BC, he advanced to suppress several apparent revolts. Starting from Amphipolis, he first went east into the country of the "Independent Thracians"; and at Mount Haemus, the Macedonian army attacked and defeated a Thracian army manning the heights.[58] The Macedonians marched on into the country of the Triballi, and proceeded to defeat the Triballian army near the Lyginus river [59] (a tributary of the Danube). Alexander then advanced for three days on to the Danube, encountering the Getae tribe on the opposite shore. Surprising the Getae by crossing the river at night, he forced the Getae army to retreat after the first cavalry skirmish, leaving their town to the Macedonian army.[60][61] News then reached Alexander that Cleitus, King of Illyria, and King Glaukias of the Taulanti were in open revolt against Macedonian authority. Marching west into Illyria, Alexander defeated each in turn, forcing Cleitus and Glaukias to flee with their armies, leaving Alexander's northern frontier secure.[62][63]

While he was triumphantly campaigning north, the Thebans and Athenians rebelled once more. Alexander reacted immediately, but, while the other cities once again hesitated, Thebes decided to resist with the utmost vigor. However, the resistance was ineffective, and the city was razed to the ground amid great bloodshed, and its territory was divided between the other Boeotian cities. The end of Thebes cowed Athens into submission, leaving all of Greece at least outwardly at peace with Alexander.[64]

Conquest of the Persian Empire

Asia Minor

Alexander's army crossed the Hellespont in 334 BC with approximately 42,000 soldiers from Macedon and various Greek city-states, mercenaries, and feudally raised soldiers from Thrace, Paionia, and Illyria.[65] After an initial victory against Persian forces at the Battle of the Granicus, Alexander accepted the surrender of the Persian provincial capital and treasury of Sardis and proceeded down the Ionian coast.[66] At Halicarnassus, Alexander successfully waged the first of many sieges, eventually forcing his opponents, the mercenary captain Memnon of Rhodes and the Persian satrap of Caria, Orontobates, to withdraw by sea.[67] Alexander left the government of Caria to Ada, who adopted Alexander as her son.[68]

From Halicarnassus, Alexander proceeded into mountainous Lycia and the Pamphylian plain, asserting control over all coastal cities. He did this to deny the Persians naval bases. Since Alexander had no reliable fleet of his own, defeating the Persian fleet required land control.[69] From Pamphylia onward, the coast held no major ports and so Alexander moved inland. At Termessos, Alexander humbled but did not storm the Pisidian city.[70] At the ancient Phrygian capital of Gordium, Alexander 'undid' the hitherto unsolvable Gordian Knot, a feat said to await the future "king of Asia".[71] According to the story, Alexander proclaimed that it did not matter how the knot was undone, and hacked it apart with his sword.[72]

The Levant and Syria

After spending the winter campaigning in Asia Minor, Alexander's army crossed the Cilician Gates in 333 BC, and defeated the main Persian army under the command of Darius III at the Battle of Issus in November.[73] Darius fled the battle, causing his army to break, and left behind his wife, his two daughters, his mother Sisygambis, and a fabulous amount of treasure.[74] He afterward offered a peace treaty to Alexander, the concession of the lands he had already conquered, and a ransom of 10,000 talents for his family. Alexander replied that since he was now king of Asia, it was he alone who decided territorial divisions.[75]

Alexander proceeded to take possession of Syria, and most of the coast of the Levant.[76] However, the following year, 332 BC, he was forced to attack Tyre, which he eventually captured after a famous siege.[77][78] After the capture of Tyre, Alexander crucified all the men of military age, and sold the women and children into slavery.[79]

Egypt

When Alexander destroyed Tyre, most of the towns on the route to Egypt quickly capitulated, with the exception of Gaza. The stronghold at Gaza was built on a hill and was heavily fortified.[80] At the beginning of the Siege of Gaza, Alexander utilized the engines he had employed against Tyre. After three unsuccessful assaults, the stronghold was finally taken by force, but not before Alexander received a serious shoulder wound. When Gaza was taken, the male population was put to the sword and the women and children were sold into slavery.[81]

Jerusalem, on the other hand, opened its gates in surrender, and according to Josephus, Alexander was shown the book of Daniel's prophecy, presumably chapter 8, where a mighty Greek king would subdue and conquer the Persian Empire. Thereupon, Alexander spared Jerusalem and pushed south into Egypt.[82][83]

Alexander advanced on Egypt in later 332 BC, where he was regarded as a liberator.[84] He was pronounced the new "master of the Universe" and son of the deity of Amun at the Oracle of Siwa Oasis in the Libyan desert.[85] Henceforth, Alexander often referred to Zeus-Ammon as his true father, and subsequent currency depicted him adorned with ram horns as a symbol of his divinity.[86][87] During his stay in Egypt, he founded Alexandria-by-Egypt, which would become the prosperous capital of the Ptolemaic Kingdom after his death.[88]

Assyria and Babylonia

Leaving Egypt in 331 BC, Alexander marched eastward into Mesopotamia (now northern Iraq) and defeated Darius once more at the Battle of Gaugamela.[89] Once again, Darius was forced to leave the field, and Alexander chased him as far as Arbela. Darius fled over the mountains to Ecbatana (modern Hamedan), and Alexander marched to and captured Babylon.[90]

Persia

From Babylon, Alexander went to Susa, one of the Achaemenid capitals, and captured its legendary treasury.[90] Sending the bulk of his army to the Persian ceremonial capital of Persepolis via the Royal Road, Alexander himself took selected troops on the direct route to the city. Alexander had to storm the pass of the Persian Gates (in the modern Zagros Mountains) which had been blocked by a Persian army under Ariobarzanes and then made a dash for Persepolis before its garrison could loot the treasury.[91] On entering Persepolis Alexander allowed his troops to loot the city, before finally calling a halt to it.[92] At Persepolis Alexander stared at the crumbled statue of Xerxes and decided to leave it on the ground.[93][94] During Alexander's stay in the capital a fire broke out in the eastern palace of Xerxes and spread to the rest of the city. Theories abound as to whether this was the result of a drunken accident, or a deliberate act of revenge for the burning of the Acropolis of Athens during the Second Persian War.[94] Arrian, in one of his infrequent criticisms of Alexander, states "I too do not think that Alexander showed good sense in this action nor that he could punish the Persians of a long past age."[95]

Fall of the Empire and the East

Alexander then set off in pursuit of Darius again, first into Media, and then Parthia.[96] The Persian king was no longer in control of his destiny, having been taken prisoner by Bessus, his Bactrian satrap and kinsman.[97] As Alexander approached, Bessus had his men fatally stab the Great King and then declared himself Darius' successor as Artaxerxes V, before retreating into Central Asia to launch a guerrilla campaign against Alexander.[98] Darius' remains were buried by Alexander next to his Achaemenid predecessors in a full regal funeral.[99] Alexander claimed that, while dying, Darius had named him as his successor to the Achaemenid throne.[100] The Achaemenid Empire is normally considered to have fallen with the death of Darius.[101]

Alexander, now considering himself the legitimate successor to Darius, viewed Bessus as a usurper to the Achaemenid throne, and set out to defeat him. This campaign, initially against Bessus, turned into a grand tour of central Asia, with Alexander founding a series of new cities, all called Alexandria, including modern Kandahar in Afghanistan, and Alexandria Eschate ("The Furthest") in modern Tajikistan. The campaign took Alexander through Media, Parthia, Aria (West Afghanistan), Drangiana, Arachosia (South and Central Afghanistan), Bactria (North and Central Afghanistan), and Scythia.[102]

Bessus was betrayed in 329 BC by Spitamenes, who held an undefined position in the satrapy of Sogdiana. Spitamenes handed over Bessus to Ptolemy, one of Alexander's trusted companions, and Bessus was executed.[103] However, when, at some point later, Alexander was on the Jaxartes dealing with an incursion by a horse nomad army, Spitamenes raised Sogdiana in revolt. Alexander personally defeated the Scythians at the Battle of Jaxartes and immediately launched a campaign against Spitamenes and defeated him in the Battle of Gabai; after the defeat, Spitamenes was killed by his own men, who then sued for peace.[104]

Problems and plots

During this time, Alexander took the Persian title "King of Kings" (Shahanshah) and adopted some elements of Persian dress and customs at his court, notably the custom of proskynesis, either a symbolic kissing of the hand, or prostration on the ground, that Persians paid to their social superiors.[105][106] The Greeks regarded the gesture as the province of deities and believed that Alexander meant to deify himself by requiring it. This cost him much in the sympathies of many of his countrymen.[106] A plot against his life was revealed, and one of his officers, Philotas, was executed for failing to bring the plot to his attention. The death of the son necessitated the death of the father, and thus Parmenion, who had been charged with guarding the treasury at Ecbatana, was assassinated by command of Alexander, so he might not make attempts at vengeance. Most infamously, Alexander personally slew the man who had saved his life at Granicus, Cleitus the Black, during a drunken argument at Maracanda.[107] Later, in the Central Asian campaign, a second plot against his life was revealed, this one instigated by his own royal pages. His official historian, Callisthenes of Olynthus (who had fallen out of favor with the king by leading the opposition to his attempt to introduce proskynesis), was accused of being implicated in the plot; however, there has never been consensus among historians regarding his involvement in the conspiracy.[108]

Indian campaign

Invasion of the Indian subcontinent

Obv: Alexander being crowned by Nike.

Rev: Alexander attacking King Porus on his elephant. British Museum.

After the death of Spitamenes and his marriage to Roxana (Roshanak in Bactrian) to cement his relations with his new Central Asian satrapies, Alexander was finally free to turn his attention to the Indian subcontinent. Alexander invited all the chieftains of the former satrapy of Gandhara, in the north of what is now Pakistan, to come to him and submit to his authority. Omphis, ruler of Taxila, whose kingdom extended from the Indus to the Hydaspes, complied, but the chieftains of some hill clans, including the Aspasioi and Assakenoi sections of the Kambojas (known in Indian texts also as Ashvayanas and Ashvakayanas), refused to submit.[109]

In the winter of 327/326 BC, Alexander personally led a campaign against these clans; the Aspasioi of Kunar valleys, the Guraeans of the Guraeus valley, and the Assakenoi of the Swat and Buner valleys.[110] A fierce contest ensued with the Aspasioi in which Alexander himself was wounded in the shoulder by a dart but eventually the Aspasioi lost the fight. Alexander then faced the Assakenoi, who fought bravely and offered stubborn resistance to Alexander in the strongholds of Massaga, Ora and Aornos.[109] The fort of Massaga could only be reduced after several days of bloody fighting in which Alexander himself was wounded seriously in the ankle. According to Curtius, "Not only did Alexander slaughter the entire population of Massaga, but also did he reduce its buildings to rubbles".[111] A similar slaughter then followed at Ora, another stronghold of the Assakenoi. In the aftermath of Massaga and Ora, numerous Assakenians fled to the fortress of Aornos. Alexander followed close behind their heels and captured the strategic hill-fort after the fourth day of a bloody fight.[109]

After Aornos, Alexander crossed the Indus and fought and won an epic battle against a local Hindu ruler Porus, who ruled a region in the Punjab, in the Battle of Hydaspes in 326 BC.[112] Alexander was greatly impressed by Porus for his bravery in battle, and therefore made an alliance with him and appointed him as satrap of his own kingdom, even adding land he did not own before. Additional reasons were probably political since, to control lands so distant from Greece required local assistance and co-operation.[113] Alexander named one of the two new cities that he founded on opposite sides of the Hydaspes river, Bucephala, in honor of the horse that had brought him to India, and had died during the battle[114] and the other Nicaea (Victory) at the site of modern day Mong.[115][116]

Revolt of the army

East of Porus' kingdom, near the Ganges River, was the powerful Nanda Empire of Magadha and Gangaridai Empire of Bengal. Fearing the prospects of facing other powerful Indian armies and exhausted by years of campaigning, his army mutinied at the Hyphasis River, refusing to march further east. This river thus marks the easternmost extent of Alexander's conquests.[117][118]

As for the Macedonians, however, their struggle with Porus blunted their courage and stayed their further advance into India. For having had all they could do to repulse an enemy who mustered only twenty thousand infantry and two thousand horse, they violently opposed Alexander when he insisted on crossing the river Ganges also, the width of which, as they learned, was thirty-two furlongs, its depth a hundred fathoms, while its banks on the further side were covered with multitudes of men-at-arms and horsemen and elephants. For they were told that the kings of the Ganderites and Praesii were awaiting them with eighty thousand horsemen, two hundred thousand footmen, eight thousand chariots, and six thousand war elephants.[117]

Alexander spoke to his army and tried to persuade them to march further into India but Coenus pleaded with him to change his opinion and return, the men, he said, "longed to again see their parents, their wives and children, their homeland". Alexander, seeing the unwillingness of his men, eventually agreed and turned south, marching along the Indus. Along the way his army conquered the Malli clans (in modern day Multan), and other Indian tribes.[119]

Alexander sent much of his army to Carmania (modern southern Iran) with his general Craterus, and commissioned a fleet to explore the Persian Gulf shore under his admiral Nearchus, while he led the rest of his forces back to Persia through the more difficult southern route along the Gedrosian Desert and Makran (now part of southern Iran and Pakistan).[120]

Last years in Persia

Discovering that many of his satraps and military governors had misbehaved in his absence, Alexander executed a number of them as examples, on his way to Susa.[121][122] As a gesture of thanks, he paid off the debts of his soldiers, and announced that he would send those over-aged and disabled veterans back to Macedon under Craterus. But, his troops misunderstood his intention and mutinied at the town of Opis, refusing to be sent away and bitterly criticizing his adoption of Persian customs and dress, and the introduction of Persian officers and soldiers into Macedonian units.[123] Alexander executed the ringleaders of the mutiny, but forgave the rank and file.[124] In an attempt to craft a lasting harmony between his Macedonian and Persian subjects, he held a mass marriage of his senior officers to Persian and other noblewomen at Susa, but few of those marriages seem to have lasted much beyond a year.[122] Meanwhile, upon his return, Alexander learned some men had desecrated the tomb of Cyrus the Great, and swiftly executed them, because they were put in charge of guarding the tomb Alexander held in honor.[125]

After Alexander traveled to Ecbatana to retrieve the bulk of the Persian treasure, his closest friend and possible lover, Hephaestion, died of an illness, or possibly of poisoning.[126][127] According to Plutarch, Alexander, distraught over the death of his longtime companion, sacked a nearby town, and put all of its inhabitants to the sword, as a sacrifice to Hephaestion's ghost.[128] Arrian finds great diversity and casts doubts on the accounts of Alexander's displays of grief, although he says that they all agree that Hephaestion's death devastated him, and that he ordered the preparation of an expensive funeral pyre in Babylon, as well as a decree for the observance of a public mourning.[126]

Back in Babylon, Alexander planned a series of new campaigns, beginning with an invasion of Arabia, but he would not have a chance to realize them.[129]

Death and succession

On either 10 or 11 June 323 BC, Alexander died in the palace of Nebuchadnezzar II, in Babylon at the age of 32.[130] Details of the death differ slightly - Plutarch's account is that roughly 14 days before his death, Alexander entertained his admiral Nearchus, and spent the night and next day drinking with Medius of Larissa.[131] He developed a fever, which grew steadily worse, until he was unable to speak, and the common soldiers, anxious about his health, demanded and were granted the right to file past him as he silently waved at them.[131][132][133] Two days later, Alexander was dead.[131][132] Diodorus recounts that Alexander was struck down with pain after downing a large bowl of unmixed wine in honour of Hercules, and died after some agony,[134] which is also mentioned as an alternative by Arrian, but Plutarch specifically denies this claim.[131]

Given the propensity of the Macedonian aristocracy to assassination,[135] allegations of foul play have been made about the death of Alexander. Diodorus, Plutarch, Arrian and Justin all mention the theory that Alexander was poisoned. Plutarch dismisses it as a fabrication,[49] while both Diodorus and Arrian say that they only mention it for the sake of completeness.[134][136] The accounts are nevertheless fairly consistent in designating Antipater, recently removed from the position of Macedonian viceroy, and at odds with Olympias, as the head of the alleged plot. Perhaps taking his summons to Babylon as a death sentence in waiting,[137] and having seen the fate of Parmenion and Philotas,[138] Antipater arranged for Alexander to be poisoned by his son Iollas, who was Alexander's wine-pourer.[49][136][138] There is even a suggestion that Aristotle may have had a hand in the plot.[49][136] Conversely, the strongest argument against the poison theory is the fact that twelve days had passed between the start of his illness and his death; in the ancient world, such long-acting poisons were probably not available.[139] In 2010, however, a theory was proposed that indicated that the circumstances of his death are compatible with poisoning by water of the river Styx (Mavroneri) that contained calicheamicin, a dangerous compound produced by bacteria present in its waters.[140]

Several natural causes (diseases) have been suggested as the cause of Alexander's death; malaria or typhoid fever are obvious candidates. A 1998 article in the New England Journal of Medicine attributed his death to typhoid fever complicated by bowel perforation and ascending paralysis,[141] whereas another recent analysis has suggested pyrogenic spondylitis or meningitis as the cause.[142] Other illnesses could have also been the culprit, including acute pancreatitis or the West Nile virus.[143][144] Natural-cause theories also tend to emphasise that Alexander's health may have been in general decline after years of heavy drinking and his suffering severe wounds (including one in India that nearly claimed his life). Furthermore, the anguish that Alexander felt after Hephaestion's death may have contributed to his declining health.[141]

Another possible cause of Alexander's death is an overdose of medication containing hellebore, which is deadly in large doses.[145][146]

Fate after death

Alexander's body was placed in a gold anthropoid sarcophagus, which was in turn placed in a second gold casket.[147] According to Aelian, a seer called Aristander foretold that the land where Alexander was laid to rest "would be happy and unvanquishable forever".[148] Perhaps more likely, the successors may have seen possession of the body as a symbol of legitimacy (it was a royal prerogative to bury the previous king).[149] At any rate, Ptolemy stole the funeral cortege, and took it to Memphis.[147][148] His successor, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, transferred the sarcophagus to Alexandria, where it remained until at least Late Antiquity. Ptolemy IX Lathyros, one of the last successors of Ptolemy I, replaced Alexander's sarcophagus with a glass one so he could melt the original down for issues of his coinage.[150] Pompey, Julius Caesar and Augustus all visited the tomb in Alexandria, the latter allegedly accidentally knocking the nose off the body. Caligula was said to have taken Alexander's breastplate from the tomb for his own use. In c. AD 200, Emperor Septimius Severus closed Alexander's tomb to the public. His son and successor, Caracalla, was a great admirer of Alexander, and visited the tomb in his own reign. After this, details on the fate of the tomb are sketchy.[150]

The so-called "Alexander Sarcophagus", discovered near Sidon and now in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum, is so named not because it was thought to have contained Alexander's remains, but because its bas-reliefs depict Alexander and his companions hunting and in battle with the Persians. It was originally thought to have been the sarcophagus of Abdalonymus (died 311 BC), the king of Sidon appointed by Alexander immediately following the battle of Issus in 331.[151][152][153] However, more recently, it has been suggested that it may date from earlier than Abdalonymus' death.[154]

Division of the empire

Alexander had no obvious or legitimate heir, his son Alexander IV by Roxane being born after Alexander's death. This left the huge question as to who would rule the newly conquered, and barely pacified empire.[155] According to Diodorus, Alexander's companions asked him when he was on his deathbed to whom he bequeathed his kingdom; his laconic reply was "tôi kratistôi"—"to the strongest".[134] Given that Arrian and Plutarch have Alexander speechless by this point, it is possible that this is an apocryphal story.[156] Diodorus, Curtius and Justin also have the more plausible story of Alexander passing his signet ring to Perdiccas, one of his bodyguard and leader of the companion cavalry, in front of witnesses, thereby possibly nominating Perdiccas as his successor.[134][155]

In any event, Perdiccas initially avoided explicitly claiming power, instead suggesting that Roxane's baby would be king, if male; with himself, Craterus, Leonnatus and Antipater as guardians. However, the infantry, under the command of Meleager, rejected this arrangement since they had been excluded from the discussion. Instead, they supported Alexander's half-brother Philip Arrhidaeus. Eventually, the two sides reconciled, and after the birth of Alexander IV, he and Philip III were appointed joint kings of the Empire—albeit in name only.[157]

It was not long, however, before dissension and rivalry began to afflict the Macedonians. The satrapies handed out by Perdiccas at the Partition of Babylon became power bases each general could use to launch his own bid for power. After the assassination of Perdiccas in 321 BC, all semblance of Macedonian unity collapsed, and 40 years of war between "The Successors" (Diadochi) ensued before the Hellenistic world settled into four stable power blocks: the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, the Seleucid Empire in the east, the Kingdom of Pergamon in Asia Minor, and Macedon. In the process, both Alexander IV and Philip III were murdered.[158]

Testament

Diodorus relates that Alexander had given detailed written instructions to Craterus some time before his death.[159] Although Craterus had already started to carry out some of Alexander's commands, the successors chose not to further implement them, on the grounds they were impractical and extravagant.[159] The testament called for military expansion into the southern and western Mediterranean, monumental constructions, and the intermixing of Eastern and Western populations. Its most remarkable items were:

- Construction of a monumental pyre to Hephaestion, costing 10,000 talents

- Construction of a monumental tomb for his father Philip, "to match the greatest of the pyramids of Egypt"

- Erection of great temples in Delos, Delphi, Dodona, Dium, Amphipolis, Cyrnus, and Ilium

- Building of "a thousand warships, larger than triremes, in Phoenicia, Syria, Cilicia, and Cyprus for the campaign against the Carthaginians and the others who live along the coast of Libya and Iberia and the adjoining coastal regions as far as Sicily"

- Building of a road in northern Africa as far as the Pillars of Heracles, with ports and shipyards along it

- Establishment of cities and the "transplant of populations from Asia to Europe and in the opposite direction from Europe to Asia, in order to bring the largest continent to common unity and to friendship by means of intermarriage and family ties."[160]

Character

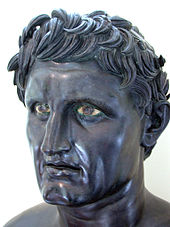

Physical appearance

Green provides a description of Alexander's appearance, based on ancient sources:

Physically, Alexander was not prepossessing. Even by Macedonian standards he was very short, though stocky and tough. His beard was scanty, and he stood out against his hirsute Macedonian barons by going clean-shaven. His neck was in some way twisted, so that he appeared to be gazing upward at an angle. His eyes (one blue, one brown) revealed a dewy, feminine quality. He had a high complexion and a harsh voice.[161]

Many descriptions and statues portray Alexander with the aforementioned gaze looking upward and outward. Both his father Philip II and his brother Philip Arrhidaeus also suffered from physical deformities, which had led to the suggestion that Alexander suffered from a congenital scoliotic disorder (familial neck and spinal deformity). Furthermore, it has been suggested that this may have contributed to his death.[142]

During his last years, sculptor Lysippus sculpted an image of Alexander. Lysippus had captured in the stone Alexander's appearance characteristics; slightly left-turned neck and peculiar gaze. Lysippus' sculpture, which is opposite to his often vigorous portrayal, especially in coinage of the time, is thought to be the most faithful depiction of Alexander.[162]

Personality

Alexander's personality is well described by the ancient sources. Some of his strongest personality traits formed in response to his parents.[161] His mother had huge ambitions for Alexander, and encouraged him to believe it was his destiny to conquer the Persian Empire.[161] Indeed, Olympias may have gone to the extent of poisoning Philip Arrhidaeus so as to disable him, and prevent him being a rival for Alexander.[49] Olympias's influence instilled huge ambition and a sense of destiny in Alexander,[163] and Plutarch tells us that his ambition "kept his spirit serious and lofty in advance of his years".[164] Alexander's relationship with his father generated the competitive side of his personality; he had a need to out-do his father, as his reckless nature in battle suggests.[161] While Alexander worried that his father would leave him "no great or brilliant achievement to be displayed to the world",[12] he still attempted to downplay his father's achievements to his companions.[161]

Alexander's most evident personality traits were his violent temper and rash, impulsive nature,[164][165] which undoubtedly contributed to some of his decisions during his life.[161] Plutarch thought that this part of his personality was the cause of his weakness for alcohol.[164] Although Alexander was stubborn and did not respond well to orders from his father, he was easier to persuade by reasoned debate.[17] Indeed, set beside his fiery temperament, there was a calmer side to Alexander; perceptive, logical, and calculating. He had a great desire for knowledge, a love for philosophy, and was an avid reader.[22] This was no doubt in part due to his tutelage by Aristotle; Alexander was intelligent and quick to learn.[17][161] The tale of his "solving" the Gordian knot neatly demonstrates this. The intelligent and rational side to Alexander is amply demonstrated by his ability and success as a general.[165] He had great self-restraint in "pleasures of the body", contrasting with his lack of self control with alcohol.[164][166]

Alexander was undoubtedly erudite, and was a patron to both the arts and sciences.[22][164] However, he had little interest in sports, or the Olympic games (unlike his father), seeking only the Homeric ideals of glory and fame.[163][164] He had great charisma and force of personality, characteristics, which made him a great leader.[155][165] This is further emphasised by the inability of any of his generals to unite the Macedonians and retain the Empire after his death – only Alexander had the personality to do so.[155]

Megalomania

During his final years, and especially after the death of Hephaestion, Alexander began to exhibit signs of megalomania and paranoia.[137] His extraordinary achievements, coupled with his own ineffable sense of destiny and the flattery of his companions, may have combined to produce this effect.[167] His delusions of grandeur are readily visible in the testament that he ordered Craterus to fulfil, and in his desire to conquer all non-Greek peoples.[137]

He seems to have come to believe himself a deity, or at least sought to deify himself.[137] Olympias always insisted to him that he was the son of Zeus,[2] a theory apparently confirmed to him by the oracle of Amun at Siwa.[86] He began to identify himself as the son of Zeus-Ammon.[86] Alexander adopted some elements of Persian dress and customs at his court, notably the custom of proskynesis, a practice of which the Macedonians disapproved, and were loath to perform.[105][106] Such behaviour cost him much in the sympathies of many of his countrymen.[106]

Personal relationships

The greatest emotional relationship of Alexander's life was with his friend, general, and bodyguard Hephaestion, the son of a Macedonian noble.[126][161][168] Hephaestion's death devastated Alexander, sending him into a period of grieving.[126][128] This event may have contributed to Alexander's failing health, and detached mental state during his final months.[137][141] Alexander married twice: Roxana, daughter of the Bactrian nobleman Oxyartes, out of love;[169] and Stateira II, a Persian princess and daughter of Darius III of Persia, as a matter of political interest.[170] He apparently had two sons, Alexander IV of Macedon of Roxana and, possibly, Heracles of Macedon from his mistress Barsine; and lost another child when Roxana miscarried at Babylon.[171][172]

Alexander's sexuality has been the subject of speculation and controversy.[173] Nowhere in the ancient sources is it stated that Alexander had homosexual relationships, or that Alexander's relationship with Hephaestion was sexual. Aelian, however, writes of Alexander's visit to Troy where "Alexander garlanded the tomb of Achilles and Hephaestion that of Patroclus, the latter riddling that he was a beloved of Alexander, in just the same way as Patroclus was of Achilles".[174] Noting that the word eromenos (ancient Greek for beloved) does not necessarily bear sexual meaning, Alexander may indeed have been bisexual, which in his time was not controversial.[175][176]

Green argues that there is little evidence in the ancient sources Alexander had much interest in women, particularly since he did not produce an heir until the very end of his life.[161] However, he was relatively young when he died, and Ogden suggests that Alexander's matrimonial record is more impressive than his father's at the same age.[177] Apart from wives, Alexander had many more female companions. Alexander had accumulated a harem in the style of Persian kings but he used it rather sparingly;[178] showing great self-control in "pleasures of the body".[166] It is possible that Alexander was simply not a highly sexed person. Nevertheless, Plutarch describes how Alexander was infatuated by Roxanne while complimenting him on not forcing himself on her.[179] Green suggests that, in the context of the period, Alexander formed quite strong friendships with women, including Ada of Caria, who adopted Alexander, and even Darius's mother Sisygambis, who supposedly died from grief when Alexander died.[161]

Legacy

Hellenistic kingdoms

Alexander's most obvious legacy was the introduction of Macedonian rule to huge new swathes of Asia. Many of these areas would remain in Macedonian hands or under Greek influence for the next 200–300 years. The successor states that emerged were, at least initially, dominant forces during this epoch, and these 300 years are often referred to as the Hellenistic period.[181]

The eastern borders of Alexander's empire began to collapse even during his lifetime.[155] However, the power vacuum he left in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent directly gave rise to one of the most powerful Indian dynasties in history. Taking advantage of the neglect shown to this region by the successors, Chandragupta Maurya (referred to in European sources as Sandrokotto), of relatively humble origin, took control of the Punjab, and then with that power base proceeded to conquer the Nanda Empire of northern India.[182] In 305 BC Seleucus, one of the successors, marched to India to reclaim the territory; instead he ceded the area to Chandragupta in return for 500 war elephants. These in turn played a pivotal role in the Battle of Ipsus the result of which did much to settle the division of the Empire.[182]

Hellenization

Hellenization is a term coined by the German historian Johann Gustav Droysen to denote the spread of Greek language, culture, and population into the former Persian empire after Alexander's conquest.[181] That this export took place is undoubted, and can be seen in the great Hellenistic cities of, for instance, Alexandria (one of around twenty towns founded by Alexander[183]), Antioch[184] and Seleucia (south of modern Baghdad).[185] However, exactly how widespread and deeply permeating this was, and to what extent it was a deliberate policy, is debatable. Alexander certainly made deliberate efforts to insert Greek elements into Persian culture and in some instances he attempted to hybridize Greek and Persian culture, culminating in his aspiration to homogenise the populations of Asia and Europe. However, the successors explicitly rejected such policies after his death. Nevertheless, Hellenization occurred throughout the region, and moreover, was accompanied by a distinct and opposite 'Orientalization' of the Successor states.[184][186]

The core of Hellenistic culture was essentially Athenian by origin.[184][187] The Athenian koine dialect had been adopted long before Philip II for official use and was thus spread throughout the Hellenistic world, becoming the lingua franca through Alexander's conquests. Furthermore, town planning, education, local government, and art current in the Hellenistic period were all based on Classical Greek ideals, evolving though into distinct new forms commonly grouped as Hellenistic.[184] Aspects of the Hellenistic culture were still evident in the traditions of the Byzantine Empire up until the mid-15th century.[188][189]

Some of the most unusual effects of Hellenization can be seen in India, in the region of the relatively late-arising Indo-Greek kingdoms.[190] There, isolated from Europe, Greek culture apparently hybridised with Indian, and especially Buddhist, influences. The first realistic portrayals of the Buddha appeared at this time; they are modelled on Greek statues of Apollo.[190] Several Buddhist traditions may have been influenced by the ancient Greek religion: the concept of Boddhisatvas is reminiscent of Greek divine heroes,[191] and some Mahayana ceremonial practices (burning incense, gifts of flowers, and food placed on altars) are similar to those practiced by the ancient Greeks. Zen Buddhism draws in part on the ideas of Greek stoics, such as Zeno.[192] One Greek king, Menander I, probably became Buddhist, and is immortalized in Buddhist literature as 'Milinda'.[190]

Influence on Rome

Alexander and his exploits were admired by many Romans who wanted to associate themselves with his achievements. Polybius started his Histories by reminding Romans of his role, and thereafter subsequent Roman leaders saw him as their inspirational role model. Julius Caesar reportedly wept in Spain at the sight of Alexander's statue, because he thought he had achieved so little by the same age that Alexander had conquered the world.[193] Pompey the Great searched the conquered lands of the east for Alexander's 260-year-old cloak, which he then wore as a sign of greatness. In his zeal to honor Alexander, Augustus accidentally broke the nose off the Macedonian's mummified corpse while laying a wreath at the Alexander's tomb Alexandria. The Macriani, a Roman family that in the person of Macrinus briefly ascended to the imperial throne, kept images of Alexander on their persons, either on jewelry, or embroidered into their clothes.[194]

In the summer of 1995, a statue of Alexander was recovered in an excavation of a Roman house in Alexandria, which was richly decorated with mosaic and marble pavements and probably was constructed in the 1st century AD and occupied until the 3rd century.[195]

Legend

There are many legendary accounts surrounding the life of Alexander the Great, with a relatively large number deriving from his own lifetime, probably encouraged by Alexander himself. His court historian Callisthenes portrayed the sea in Cilicia as drawing back from him in proskynesis. Writing shortly after Alexander's death, another participant, Onesicritus, went so far as to invent a tryst between Alexander and Thalestris, queen of the mythical Amazons. When Onesicritus read this passage to his patron, Alexander's general and later King Lysimachus reportedly quipped, "I wonder where I was at the time."[196]

In the first centuries after Alexander's death, probably in Alexandria, a quantity of the more legendary material coalesced into a text known as the Alexander Romance, later falsely ascribed to the historian Callisthenes and therefore known as Pseudo-Callisthenes. This text underwent numerous expansions and revisions throughout Antiquity and the Middle Ages.[197]

There is also an Iranian or Persian account of Alexander the Great in "Shahnameh" or "The Epic of the Kings" by Ferdowsi. It is called Eskandarnameh.[198] It speaks of Alexander being the son of Nahid (Lydia) and being sent back to Philip of Macedon because she had bad breath. Later it is mentioned that the name Eskandar was given because the remedy it provided for his mother. Arab historians then referred to him as al-Iskandar.

In ancient and modern culture

Alexander the Great's accomplishments and legacy have been preserved and depicted in many ways. Alexander has figured in works of both high and popular culture from his own era to the modern day. In the Middle Ages he was created a member of the Nine Worthies, a group of heroes encapsulating all the ideal qualities of chivalry.

In Punjab, the land of his final conquest, the name "Secunder" is commonly given to children even today. This is both due to respect and admiration for Alexander and also as a memento to the fact that fighting the people of Punjab fatigued his army to the point that they revolted against him.

A common proverb in the Punjab reads jit jit key jung, secunder jay haar, in translation, "Alexander wins so many battles that he loses the war". It is used to address anyone who is good at winning but never takes advantage of those wins.[citation needed]

Sources

Texts written by people who actually knew Alexander or who gathered information from men who served with Alexander are all lost apart from a few inscriptions and fragments. Contemporaries who wrote accounts of his life include Alexander's campaign historian Callisthenes; Alexander's generals Ptolemy and Nearchus; Aristobulus, a junior officer on the campaigns; and Onesicritus, Alexander's chief helmsman. These works have been lost, but later works based on these original sources survive. The five main surviving accounts are by Arrian, Curtius, Plutarch, Diodorus, and Justin.[199]

Ancestry

| Family of Alexander the Great | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

Notes

^ i: By the time of his death, he had conquered the entire Achaemenid Persian Empire, adding it to Macedon's European territories; according to some modern writers, this was most of the world then known to the ancient Greeks (the 'Ecumene').[200][201] An approximate view of the world known to Alexander can be seen in Hecataeus of Miletus's map, see File:Hecataeus world map-en.svg.

^ ii: For instance, Hannibal supposedly ranked Alexander as the greatest general;[202] Julius Caesar wept on seeing a statue of Alexander, since he had achieved so little by the same age;[193] Pompey consciously posed as the 'new Alexander';[203] the young Napoleon Bonaparte also encouraged comparisons with Alexander.[204]

^ iii: The name Αλέξανδρος derives from the Greek verb "ἀλέξω" (alexō), "to ward off, to avert, to defend"[205] and the noun "ἀνδρός" (andros), genitive of "ἀνήρ" (anēr), "man"[206] and means "protector of men."[207]

^ iv: "In the early 5th century the royal house of Macedon, the Temenidae, was recognised as Greek by the Presidents of the Olympic Games. Their verdict was and is decisive. It is certain that the Kings considered themselves to be of Greek descent from Heracles son of Zeus."[208]

^ v: "AEACIDS Descendants of Aeacus, son of Zeus and the nymph Aegina, eponymous (see the term) to the island of that name. His son was Peleus, father of Achilles, whose descendants (real or supposed) called themselves Aeacids: thus Pyrrhus and Alexander the Great."[209]

^ vi: There have been, since the time, many suspicions that Pausanias was actually hired to murder Philip. Suspicion has fallen upon Alexander, Olympias and even the newly crowned Persian Emperor, Darius III. All three of these people had motive to have Philip murdered.[210]

References

- ^ a b Yenne, W. Alexander the Great: Lessons from History's Undefeated General. Palmgrave McMillan, 2010. 244 p.

- ^ a b c Plutarch, Alexander, 3

- ^ Alexander was born on the 6 of the month Hekatombaion "The birth of Alexander at Livius.org".

- ^ a b c Plutarch, Alexander, 2

- ^ McCarty, p. 10.

- ^ a b Renault, p. 28.

- ^ Durant, Life of Greece, p. 538.

- ^ Plutarch. "Life of Pyrrhus". Penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- ^ Appian, History of the Syrian Wars, §10 and §11 at Livius.org

- ^ Bose, p. 21.

- ^ Renault, pp. 33–34.

- ^ a b Plutarch, Alexander, 5

- ^ Plutarch, Alexander, 6

- ^ Fox, The Search For Alexander, p. 64.

- ^ Renault, p. 39.

- ^ Durant, p. 538.

- ^ a b c Plutarch, Alexander, 7

- ^ Fox, The Search For Alexander, p. 65.

- ^ Renault, p. 44.

- ^ McCarty, p. 15.

- ^ Fox, The Search For Alexander, pp. 65–66.

- ^ a b c Plutarch, Alexander, 8

- ^ Renault, pp. 45–47.

- ^ McCarty, Alexander the Great, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d Plutarch, Alexander, 9

- ^ Fox, The Search For Alexander, p. 68.

- ^ Renault, p. 47.

- ^ Bose, p. 43.

- ^ Renault, pp. 47–49.

- ^ Renault, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Bose, pp. 44–45

- ^ McCarty, p. 23

- ^ Renault, p. 51.

- ^ Bose, p. 47.

- ^ McCarty, p. 24.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Library XVI, 86

- ^ "History of Ancient Sparta". Sikyon.com. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- ^ Renault, p. 54.

- ^ McCarty, p. 26.

- ^ a b McCarty, p. 27.

- ^ Bose, p. 75.

- ^ Renault, p. 56

- ^ Renault, p. 59.

- ^ Fox, The Search For Alexander, p. 71.

- ^ a b McCarty, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Renault, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Fox, The Search For Alexander, p. 72.

- ^ Green, Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age, pp5–6

- ^ a b c d e Plutarch, Alexander, 77

- ^ Renault, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Fox, p. 72.

- ^ McCarty, p. 31.

- ^ a b Renault, p. 72.

- ^ Fox, The Search For Alexander, p. 104.

- ^ Bose, p. 95.

- ^ Stoneman, page 21

- ^ Bose, p. 96.

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri I, 1

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri I, 2

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri I, 3–4

- ^ Renault, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri I, 5–6

- ^ Renault, p. 77.

- ^ Plutarch, Phocion, 17

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri I, 11

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri I, 13–19

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri I, 20–23

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri I, 23

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri I, 20, 24–26

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri I, 27–28

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri II, 3

- ^ Greene, p. 351

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri II, 6–10

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri II, 11–12

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri I, 3–4 II, 14

- ^ Arrian Anabasis Alexandri II, 23

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri II, 16–24

- ^ Gunther, p. 84.

- ^ Sabin et al., p. 396.

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri II, 26

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri II, 26–27

- ^ Josephus, Jewish Antiquities, XI, 337 [viii, 5]

- ^ Insight on the Scriptures, Volume 1, 1988, Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania International Bible Students Association, pg. 70

- ^ Ring et al. pp. 49, 320.

- ^ Grimal, p. 382.

- ^ a b c Plutarch, Alexander, 27

- ^ "Coin: from the Persian Wars to Alexander the Great, 490–336 bc". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2009-11-16.

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri III, 1

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri III 7–15

- ^ a b Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri III, 16

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri III, 18

- ^ Laura Foreman (2004). Alexander the conqueror: the epic story of the warrior king, Volume 2003. Da Capo Press. p. 152.

- ^ Plutarch, Alexander, 37

- ^ a b Hammond, N. G. L. (1983). Sources for Alexander the Great. Cambridge University Press. pp. 72–73. ISBN 9780521714716.

- ^ John Maxwell O'Brien (1994). Alexander the Great: the invisible enemy : a biography. Psychology Press. p. 104.

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri III, 19–20

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri III, 21

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri III, 21, 25

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri III, 22

- ^ Gergel, p. 81.

- ^ "The end of Persia". www.livius.org. Retrieved 2009-11-16.

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri III, 23–25, 27–30; IV, 1–7

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri III, 30

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri IV, 5–6, 16–17

- ^ a b Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri VII, 11

- ^ a b c d Plutarch, Alexander, 45

- ^ Gergel, p. 99.

- ^ Waldemar Heckel, Lawrence A. Tritle, ed. (2009). Alexander the Great: A New History. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 47–48. ISBN 9781405130820.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Tripathi (1999). History of Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 118–121. ISBN 9788120800182.

- ^ Narain, pp. 155–165

- ^ Curtius in McCrindle, Op cit, p 192, J. W. McCrindle; History of Punjab, Vol I, 1997, p 229, Punajbi University, Patiala, (Editors): Fauja Singh, L. M. Joshi; Kambojas Through the Ages, 2005, p 134, Kirpal Singh.

- ^ Tripathi (1999). History of Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 124–125. ISBN 9788120800182.

- ^ Tripathi (1999). History of Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 126–127. ISBN 9788120800182.

- ^ Gergel, p. 120.

- ^ "The encyclopædia britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information, Volume 14 p. 398". Books.google.ca. Retrieved 2011-01-29.

- ^ Alexander the Great: a reader Author Ian Worthington Editor Ian Worthington Edition illustrated, reprint Publisher Routledge, 2003ISBN 0415291860, ISBN 9780415291866 Length 332 pages p. 175

- ^ a b Plutarch, Alexander, 62

- ^ Tripathi (1999). History of Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 129–130. ISBN 9788120800182.

- ^ Tripathi (1999). History of Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 137–138. ISBN 9788120800182.

- ^ Tripathi (1999). History of Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 141. ISBN 9788120800182.

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri VI, 27

- ^ a b Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri VII, 4

- ^ Worthington, Alexander the Great, pp. 307–308

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri VII, 8

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri VI, 29

- ^ a b c d Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri VII, 14

- ^ Grant Berkley (2006). Moses in the Hieroglyphs. Trafford Publishing. p. 101. ISBN 1412056004. Retrieved 2011-01-13.

- ^ a b Plutarch, Alexander, 72

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri VII, 19

- ^ Depuydt L. "The Time of Death of Alexander the Great: 11 June 323 BC, ca. 4:00–5:00 PM". Die Welt des Orients. 28: 117–135.

- ^ a b c d Plutarch, Alexander, 75

- ^ a b Plutarch, Alexander, 76

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri VII, 26

- ^ a b c d Diodorus Siculus Library XVII, 117

- ^ Green, Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b c Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri VII, 27

- ^ a b c d e Green, Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age, pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b Diodorus Siculus Library XVII, 118

- ^ Fox, Alexander the Great, p.

- ^ "Alexander the Great poisoned by the River Styx.html". August 4, 2010. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ a b c Oldach DW, Richard RE, Borza EN, Benitez RM (1998). "A mysterious death". N. Engl. J. Med. 338 (24): 1764–1769. doi:10.1056/NEJM199806113382411. PMID 9625631.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Ashrafian, H (2004). "The death of Alexander the Great—a spinal twist of fate". J Hist Neurosci. 13 (2): 138–142. doi:10.1080/0964704049052157. PMID 15370319.

- ^ "Alexander the Great and West Nile Virus Encephalitis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ^ Sbarounis CN (2007). "Did Alexander the Great die of acute pancreatitis?". J Clin Gastroenterol. 24 (4): 294–296. doi:10.1097/00004836-199706000-00031. PMID 9252868.

- ^ Cawthorne (2004), s. 138

- ^ "Forensic Psychiatry & Medicine – Dead Men Talking". Forensic-psych.com. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ a b "HEC". Greece.org. Archived from the original on 2004-05-31. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ a b Aelian, Varia Historia XII, 64

- ^ Green, Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age, p. 32.

- ^ a b "HEC". Greece.org. Archived from the original on 2004-08-27. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ Studniczka pp. 226ff.

- ^ Beazley and Ashmole, p. 59, fig. 134.

- ^ Bieber M (1965). "The Portraits of Alexander". Greece & Rome, Second Series. 12.2: 183–188.

- ^ See Alexander Sarcophagus.

- ^ a b c d e Green, Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age, pp. 24–26.

- ^ Green, Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age, p. 20.

- ^ Green, Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age, pp. 26–29.

- ^ Green, Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age, pp. 29–45.

- ^ a b Diodorus Siculus, Library XVIII, 4

- ^ Paul McKechnie (1989). Outsiders in the Greek cities in the fourth century B.C. Taylor & Francis. p. 54. ISBN 0415003407. Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Green, Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Boswroth p.19-20

- ^ a b Green, Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f Plutarch, Alexander, 4

- ^ a b c Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri VII, 29

- ^ a b Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri VII, 28

- ^ Green, Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age, pp20–21

- ^ Diodorus Siculus Library XVII, 114

- ^ Plutarch, Alexander, 47

- ^ Plutarch, On the Fortune and Virtue of Alexander, Or2.6

- ^ "Alexander IV". livius.org. Retrieved 13 December 2009.

- ^ Renault, p. 100.

- ^ Ogden, p. 204.

- ^ Aelian, Varia Historia XII, 7

- ^ Sacks et al, p. 16.

- ^ Worthington, p. 159.

- ^ Ogden, Alexander the Great – A new history p. 208. "three attested pregnancies in eight years produces an attested impregnation rate of one every 2.7 years, which is actually superior to that of his father's.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Library XVII, 77

- ^ Plutarch, On the Fortune and Virtue of Alexander I, 11

- ^ "Source". Henry-davis.com. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- ^ a b Green, Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age, pp. xii–xix.

- ^ a b Keay, pp. 82–85.

- ^ "Alexander the Great: his towns". livius.org. Retrieved 13 December 2009.

- ^ a b c d Green, Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age, pp. 56–59.

- ^ "Seleucia on the Tigris, Iraq", University of Michigan.

- ^ Green, Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age, p. 21.

- ^ Murphy, p. 17.

- ^ Gabriel, Richard A. (2002). "The army of Byzantium". The Great Armies of Antiquity. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 277. ISBN 0275978095.

- ^ Baynes, Norman G. (2007). "Byzantine art". Byzantium: An Introduction to East Roman Civilization. Baynes Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-1406756593.

- ^ a b c Keay, pp. 101–109.

- ^ Luniya, p. 312.

- ^ Pratt, p. 237.

- ^ a b Plutarch, Caesar, 11

- ^ Holt, p. 3.

- ^ "Salima Ikram. Nile Currents". Egyptology.com. Archived from the original on 2008-02-09. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- ^ Plutarch, Alexander, 46

- ^ Stoneman, Richard (2008). Alexander the Great: A Life in Legend. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11203-0.

- ^ "Eskandarnameh". Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 2011-01-29.

- ^ Green, Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age, pp. xxii–xxviii.

- ^ Danforth, pp38, 49, 167

- ^ Stoneman, p2

- ^ Goldsworthy, pp. 327–328.

- ^ Holland, pp. 176–183.

- ^ Barnett, p. 45.

- ^ ἀλέξω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ ἀνήρ, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ "Alexander". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2009-12-11.

- ^ Hammond, N.G.L. A History of Greece to 323 BC. Cambridge University, 1986, p. 516.

- ^ Chamoux, François and Roussel, Michel. Hellenistic Civilization. Blackwell Publishing, 2003, p. 396, ISBN 0631222421.

- ^ Fox, The Search For Alexander, pp. 72–73.

- Bibliography

- Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri (The Campaigns of Alexander), translated by Aubrey de Sélincourt: Arrian ; translated (1976). The campaigns of Alexander. Penguin. ISBN 0140442537.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Curtius Rufus, Historiae Alexandri Magni (History of Alexander the Great), "Curtius Rufus, History of Alexander the Great". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 16 November 2009. Template:En icon

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica, (Library of History), translated by C.H. Oldfather (1989), "Diodorus Siculus, Library". perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 14 November 2009. Template:En icon

- Justin, Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus, translated by Rev. John Selby Watson (1853), "Justin: Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus". forumromanum.org. Retrieved 14 November 2009. Template:En icon

- Plutarch, Alexander, translated by Bernadotte Perrin (1919), "Plutarch, Alexander (English).: Alexander (ed. Bernadotte Perrin)". perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 14 November 2009. Template:En icon

- Plutarch, Moralia, Fortuna Alexandri (On the Fortune or Virtue of Alexander), translated by Bill Thayer, "Plutarch, On the Fortune of Alexander". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 14 November 2009. Template:En icon

- Barnett, C. (1997). Bonaparte. Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 1853266787.

- Beazley JD and Ashmole B (1932). Greek Sculpture and Painting. Cambridge University Press.

- Bose, Partha (2003). Alexander the Great's Art of Strategy. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1741141133.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|isbn-status=ignored (help) - Bowra, Maurice (1994). The Greek Experience. Phoenix Books. ISBN 1857991222.

- Danforth, Loring M. (1997). The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691043566.

- Durant, Will (1966). The Story of Civilization: The Life of Greece. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671418009.

- Bill Fawcett, (2006). Bill Fawcett (ed.). How To Loose A Battle: Foolish Plans and Great Military Blunders. Harper. ISBN 0060760249.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - Gergel, Tania (editor) (2004). The Brief Life and Towering Exploits of History's Greatest Conqueror as Told By His Original Biographers. Penguin Books. ISBN 0142001406.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Green, Peter (1992). Alexander of Macedon: 356–323 B.C. A Historical Biography. University of California Press. ISBN 0520071662.

- Green, Peter (2007). Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age. Orion Books. ISBN 9780753824139.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|isbn-status=ignored (help) - Greene, Robert (2000). The 48 Laws of Power. Penguin Books. p. 351. ISBN 0140280197.

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt (reprint ed.). Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9780631193960.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - Gunther, John (2007). Alexander the Great. Sterling. ISBN 1402745192.

- Hammond, N. G. L. (1989). The Macedonian State: Origins, Institutions, and History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198148836.

- Holland, T. (2003). Rubicon: Triumph and Tragedy in the Roman Republic. Abacus. ISBN 9780349115634.

- Holt, Frank Lee (2003). Alexander the Great and the mystery of the elephant medallions. University of California Press. ISBN 0520238818.

- Keay, John (2001). India: A History. Grove Press. ISBN 0802137970.

- Lane Fox, Robin (1973). Alexander the Great. Allen Lane. ISBN 0860077071.

- Lane Fox, Robin (1980). The Search for Alexander. Little Brown & Co. Boston. ISBN 0316291080.

- Goldsworthy, A. (2003). The Fall of Carthage. Cassel. ISBN 0304366420.

- Luniya, Bhanwarlal Nathuram (1978). Life and Culture in Ancient India: From the Earliest Times to 1000 A.D. Lakshmi Narain Agarwal. LCCN 78907043.

- McCarty, Nick (2004). Alexander the Great. Penguin. ISBN 0670042684.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|isbn-status=ignored (help) - Murphy, James Jerome (2003). A Synoptic History of Classical Rhetoric. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. p. 17. ISBN 1880393352.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Nandan, Y and Bhavan, BV (2003). British Death March Under Asiatic Impulse: Epic of Anglo-Indian Tragedy in Afghanistan. Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. ISBN 8172763018.