Global surface temperature (GST) refers to the average temperature of Earth's surface. It is determined nowadays by measuring the temperatures over the ocean and land, and then calculating a weighted average. The temperature over the ocean is called the sea surface temperature. The temperature over land is called the surface air temperature. Temperature data comes mainly from weather stations and satellites. To estimate data in the distant past, proxy data can be used for example from tree rings, corals, and ice cores.[1] Observing the rising GST over time is one of the many lines of evidence supporting the scientific consensus on climate change, which is that human activities are causing climate change.

Alternative terms for the same thing are global mean surface temperature (GMST) or global average surface temperature.

Series of reliable temperature measurements in some regions began in the 1850—1880 time frame (this is called the instrumental temperature record). Through 1940, the average annual temperature increased, but was relatively stable between 1940 and 1975. Since 1975, it has increased by roughly 0.15 °C to 0.20 °C per decade, to at least 1.1 °C (1.9 °F) above 1880 levels.[3] The current annual GMST is about 15 °C (59 °F),[4] though monthly temperatures can vary almost 2 °C (4 °F) above or below this figure.[5]

Definition

The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report defines global mean surface temperature (GMST) as follows: GMST is the "estimated global average of near-surface air temperatures over land and sea ice, and sea surface temperature (SST) over ice-free ocean regions, with changes normally expressed as departures from a value over a specified reference period".[6]: 2231

In comparison, the global mean surface air temperature (GSAT) is the "global average of near-surface air temperatures over land, oceans and sea ice. Changes in GSAT are often used as a measure of global temperature change in climate models."[6]: 2231

Relevance

Changes in global temperatures over the past century provide evidence for the effects of increasing greenhouse gases. When the climate system reacts to such changes, climate change follows. Measurement of the GST(global surface temperature) is one of the many lines of evidence supporting the scientific consensus on climate change, which is that humans are causing warming of Earth's climate system.

Measurement and calculation

The global surface temperature (GST) is calculated by averaging the temperatures over sea (sea surface temperature) and land (surface air temperature).

Instrumental temperature records are based on direct, instrument-based measurements of air temperature and ocean temperature, unlike indirect reconstructions using climate proxy data such as from tree rings and ocean sediments.[8] The longest-running temperature record is the Central England temperature data series, which starts in 1659. The longest-running quasi-global records start in 1850.[9] Temperatures on other time scales are explained in global surface temperature.

Global temperature can have different definitions. There is a small difference between air and surface temperatures.[10]: 12Observations

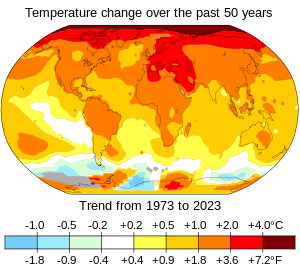

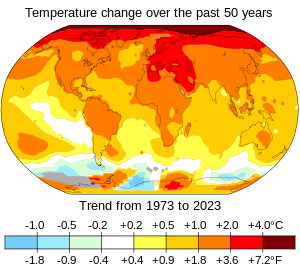

Global warming affects all parts of Earth's climate system.[12] Global surface temperatures have risen by 1.1 °C (2.0 °F). Scientists say they will rise further in the future.[13][14] The changes in climate are not uniform across the Earth. In particular, most land areas have warmed faster than most ocean areas. The Arctic is warming faster than most other regions.[15] Night-time temperatures have increased faster than daytime temperatures.[16] The impact on nature and people depends on how much more the Earth warms.[17]: 787

Scientists use several methods to predict the effects of human-caused climate change. One is to investigate past natural changes in climate.[18] To assess changes in Earth's past climate scientists have studied tree rings, ice cores, corals, and ocean and lake sediments.[19] These show that recent temperatures have surpassed anything in the last 2,000 years.[20] By the end of the 21st century, temperatures may increase to a level last seen in the mid-Pliocene. This was around 3 million years ago.[21]: 322 At that time, mean global temperatures were about 2–4 °C (3.6–7.2 °F) warmer than pre-industrial temperatures. The global mean sea level was up to 25 metres (82 ft) higher than it is today.[22]: 323 The modern observed rise in temperature and CO2 concentrations has been rapid. even abrupt geophysical events in Earth's history do not approach current rates.[23]: 54Effects

Effects of climate change are well documented and growing for Earth's natural environment and human societies. Changes to the climate system include an overall warming trend, changes to precipitation patterns, and more extreme weather. As the climate changes it impacts the natural environment with effects such as more intense forest fires, thawing permafrost, and desertification. These changes impact ecosystems and societies, and can become irreversible once tipping points are crossed. Climate activists are engaged in a range of activities around the world that seek to ameloriate these issues or prevent them from happening.[24]

The effects of climate change vary in timing and location. Up until now the Arctic has warmed faster than most other regions due to climate change feedbacks.[15] Surface air temperatures over land have also increased at about twice the rate they do over the ocean, causing intense heat waves. These temperatures would stabilize if greenhouse gas emissions were brought under control. Ice sheets and oceans absorb the vast majority of excess heat in the atmosphere, delaying effects there but causing them to accelerate and then continue after surface temperatures stabilize. Sea level rise is a particular long term concern as a result. The effects of ocean warming also include marine heatwaves, ocean stratification, deoxygenation, and changes to ocean currents.[25]: 10 The ocean is also acidifying as it absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.[26]

The ecosystems most immediately threatened by climate change are in the mountains, coral reefs, and the Arctic. Excess heat is causing environmental changes in those locations that exceed the ability of animals to adapt.[27] Species are escaping heat by migrating towards the poles and to higher ground when they can.[28] Sea level rise threatens coastal wetlands with flooding. Decreases in soil moisture in certain locations can cause desertification and damage ecosystems like the Amazon Rainforest.[29]: 9 At 2 °C (3.6 °F) of warming, around 10% of species on land would become critically endangered.[30]: 259Global temperature record

The global temperature record shows the fluctuations of the temperature of the atmosphere and the oceans through various spans of time. There are numerous estimates of temperatures since the end of the Pleistocene glaciation, particularly during the current Holocene epoch. Some temperature information is available through geologic evidence, going back millions of years. More recently, information from ice cores covers the period from 800,000 years before the present time until now. A study of the paleoclimate covers the time period from 12,000 years ago to the present. Tree rings and measurements from ice cores can give evidence about the global temperature from 1,000-2,000 years before the present until now. The most detailed information exists since 1850, when methodical thermometer-based records began. Modifications on the Stevenson-type screen were made for uniform instrument measurements around 1880.[31]

Geologic evidence (millions of years)

On longer time scales, sediment cores show that the cycles of glacials and interglacials are part of a deepening phase within a prolonged ice age that began with the glaciation of Antarctica approximately 40 million years ago. This deepening phase, and the accompanying cycles, largely began approximately 3 million years ago with the growth of continental ice sheets in the Northern Hemisphere. Gradual changes in Earth's climate of this kind have been frequent during the existence of planet Earth. Some of them are attributed to changes in the configuration of continents and oceans due to continental drift.[citation needed]

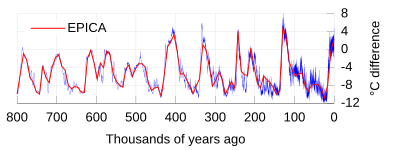

Ice cores (from 800,000 years before present)

Even longer term records exist for few sites: the recent Antarctic EPICA core reaches 800 kyr; many others reach more than 100,000 years. The EPICA core covers eight glacial/interglacial cycles. The NGRIP core from Greenland stretches back more than 100 kyr, with 5 kyr in the Eemian interglacial. Whilst the large-scale signals from the cores are clear, there are problems interpreting the detail, and connecting the isotopic variation to the temperature signal.

Ice core locations

The World Paleoclimatology Data Center (WDC) maintains the ice core data files of glaciers and ice caps in polar and low latitude mountains all over the world.

Ice core records from Greenland

As a paleothermometry, the ice core in central Greenland showed consistent records on the surface-temperature changes.[35] According to the records, changes in global climate are rapid and widespread. Warming phase only needs simple steps, however, the cooling process requires more prerequisites and bases.[36] Also, Greenland has the clearest record of abrupt climate changes in the ice core, and there are no other records that can show the same time interval with equally high time resolution.[35]

When scientists explored the trapped gas in the ice core bubbles, they found that the methane concentration in Greenland ice core is significantly higher than that in Antarctic samples of similar age, the records of changes of concentration difference between Greenland and Antarctic reveal variation of latitudinal distribution of methane sources.[37] Increase in methane concentration shown by Greenland ice core records implies that the global wetland area has changed greatly over past years.[38] As a component of greenhouse gases, methane plays an important role in global warming. The variation of methane from Greenland records makes a unique contribution for global temperature records undoubtedly.

Ice core records from Antarctica

The Antarctic ice sheet originated in the late Eocene, the drilling has restored a record of 800,000 years in Dome Concordia, and it is the longest available ice core in Antarctica. In recent years, more and more new studies have provided older but discrete records.[39] Due to the uniqueness of the Antarctic ice sheet, the Antarctic ice core not only records the global temperature changes, but also contains huge quantities of information about the global biogeochemical cycles, climate dynamics and abrupt changes in global climate.[40]

By comparing with current climate records, the ice core records in Antarctica further confirm that polar amplification.[41] Although Antarctica is covered by the ice core records, the density is rather low considering the area of Antarctica. Exploring more drilling stations is the primary goal for current research institutions.

Ice core records from low-latitude regions

The ice core records from low-latitude regions are not as common as records from polar regions, however, these records still provide much useful information for scientists. Ice cores in low-latitude regions usually locates in high altitude areas. The Guliya record is the longest record from low-latitude, high altitude regions, which spans over 700,000 years.[42] According to these records, scientists found the evidence which can prove the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) was colder in the tropics and subtropics than previously believed.[43] Also, the records from low-latitude regions helped scientists confirm that the 20th century was the warmest period in the last 1000 years.[42]

Paleoclimate (from 12,000 years before present)

Many estimates of past temperatures have been made over Earth's history. The field of paleoclimatology includes ancient temperature records. As the present article is oriented toward recent temperatures, there is a focus here on events since the retreat of the Pleistocene glaciers. The 10,000 years of the Holocene epoch covers most of this period, since the end of the Northern Hemisphere's Younger Dryas millennium-long cooling. The Holocene Climatic Optimum was generally warmer than the 20th century, but numerous regional variations have been noted since the start of the Younger Dryas.

Tree rings and ice cores (from 1,000–2,000 years before present)

Proxy measurements can be used to reconstruct the temperature record before the historical period. Quantities such as tree ring widths, coral growth, isotope variations in ice cores, ocean and lake sediments, cave deposits, fossils, ice cores, borehole temperatures, and glacier length records are correlated with climatic fluctuations. From these, proxy temperature reconstructions of the last 2000 years have been performed for the northern hemisphere, and over shorter time scales for the southern hemisphere and tropics.[44][45][46]

Geographic coverage by these proxies is necessarily sparse, and various proxies are more sensitive to faster fluctuations. For example, tree rings, ice cores, and corals generally show variation on an annual time scale, but borehole reconstructions rely on rates of thermal diffusion, and small scale fluctuations are washed out. Even the best proxy records contain far fewer observations than the worst periods of the observational record, and the spatial and temporal resolution of the resulting reconstructions is correspondingly coarse. Connecting the measured proxies to the variable of interest, such as temperature or rainfall, is highly non-trivial. Data sets from multiple complementary proxies covering overlapping time periods and areas are reconciled to produce the final reconstructions.[46][47]

Proxy reconstructions extending back 2,000 years have been performed, but reconstructions for the last 1,000 years are supported by more and higher quality independent data sets. These reconstructions indicate:[46]

- global mean surface temperatures over the last 25 years have been higher than any comparable period since AD 1600, and probably since AD 900

- there was a Little Ice Age centered on AD 1700

- there was a Medieval Warm Period centered on AD 1000, but this was not a global phenomenon.[48]

Indirect historical proxies

As well as natural, numerical proxies (tree-ring widths, for example) there exist records from the human historical period that can be used to infer climate variations, including: reports of frost fairs on the Thames; records of good and bad harvests; dates of spring blossom or lambing; extraordinary falls of rain and snow; and unusual floods or droughts.[49] Such records can be used to infer historical temperatures, but generally in a more qualitative manner than natural proxies.

Recent evidence suggests that a sudden and short-lived climatic shift between 2200 and 2100 BCE occurred in the region between Tibet and Iceland, with some evidence suggesting a global change. The result was a cooling and reduction in precipitation. This is believed to be a primary cause of the collapse of the Old Kingdom of Egypt.[50]

Instrumental temperature records (1850–present)

The instrumental temperature record is a record of temperatures within Earth's climate based on direct measurement of air temperature and ocean temperature. Instrumental temperature records do not use indirect reconstructions using climate proxy data such as from tree rings and marine sediments.[8] Instead, data is collected from thousands of meteorological stations, buoys and ships around the globe. Areas that are densely populated tend to have a high density of measurement points. In contrast, temperature observations are more spread out in sparsely populated areas such as polar regions and deserts, as well as in many regions of Africa and South America.[52] In the past, thermometers were read manually to record temperatures. Nowadays, measurements are usually connected with electronic sensors which transmit data automatically. Surface temperature data is usually presented as anomalies rather than as absolute values. A temperature anomaly is presented compared to a reference value, also called baseline period or long-term average, usually a period of 30 years. For example, a commonly used baseline period is the time period from 1951 to 1980.

The longest-running temperature record is the Central England temperature data series, which starts in 1659. The longest-running quasi-global records start in 1850.[9] For temperature measurements in the upper atmosphere a variety of methods can be used. This includes radiosondes launched using weather balloons, a variety of satellites, and aircraft.[53] Satellites can monitor temperatures in the upper atmosphere but are not commonly used to measure temperature change at the surface. Ocean temperatures at different depths are measured to add to global surface temperature datasets. This data is also used to calculate the ocean heat content.

The data clearly shows a rising trend in global average surface temperatures (i.e. global warming) and this is due to emissions of greenhouse gases from human activities. The global average and combined land and ocean surface temperature show a warming of 1.09 °C (range: 0.95 to 1.20 °C) from 1850–1900 to 2011–2020, based on multiple independently produced datasets.[54]: 5 The trend is faster since 1970s than in any other 50-year period over at least the last 2000 years.[54]: 8 Within that upward trend, some variability in temperatures happens because of natural internal variability (for example due to El Niño–Southern Oscillation).See also

- Climate change

- Climate variability and change

- Global surface temperature

- Dendroclimatology

- Instrumental temperature record

- Temperature anomaly

External links

- Hadley Centre: Global temperature data

- NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) — Global Temperature Trends.

- Surface Temperature Reconstructions for the last 2,000 Years

References

- ^ a b PAGES 2k Consortium (2019). "Consistent multidecadal variability in global temperature reconstructions and simulations over the Common Era". Nature Geoscience. 12 (8): 643–649. doi:10.1038/s41561-019-0400-0. ISSN 1752-0894. PMC 6675609. PMID 31372180.

- ^ "Global Annual Mean Surface Air Temperature Change". NASA. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- ^ World of change: Global Temperatures Archived 2019-09-03 at the Wayback Machine The global mean surface air temperature for the period 1951-1980 was estimated to be 14 °C (57 °F), with an uncertainty of several tenths of a degree.

- ^ "Solar System Temperatures". National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). 4 September 2023. Archived from the original on 1 October 2023. (link to NASA graphic)

- ^ "Tracking breaches of the 1.5 °C global warming threshold". Copernicus Programme. 15 June 2023. Archived from the original on 14 September 2023.

- ^ a b IPCC, 2021: Annex VII: Glossary [Matthews, J.B.R., V. Möller, R. van Diemen, J.S. Fuglestvedt, V. Masson-Delmotte, C. Méndez, S. Semenov, A. Reisinger (eds.)]. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 2215–2256, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.022.

- ^ "GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (v4)". NASA. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ a b "What Are "Proxy" Data?". NCDC.NOAA.gov. National Climatic Data Center, later called the National Centers for Environmental Information, part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2014. Archived from the original on 10 October 2014.

- ^ a b Brohan, P.; Kennedy, J. J.; Harris, I.; Tett, S. F. B.; Jones, P. D. (2006). "Uncertainty estimates in regional and global observed temperature changes: a new dataset from 1850". J. Geophys. Res. 111 (D12): D12106. Bibcode:2006JGRD..11112106B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.184.4382. doi:10.1029/2005JD006548. S2CID 250615.

- ^ IPCC (2018). "Summary for Policymakers" (PDF). Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. pp. 3–24.

- ^ "GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (v4)". NASA. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ Kennedy, John; Ramasamy, Selvaraju; Andrew, Robbie; Arico, Salvatore; Bishop, Erin; Braathen, Geir (2019). WMO statement on the State of the Global Climate in 2018. Geneva: Chairperson, Publications Board, World Meteorological Organization. p. 6. ISBN 978-92-63-11233-0. Archived from the original on 12 November 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ "Summary for Policymakers". Synthesis report of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (PDF). 2023. A1, A4.

- ^ State of the Global Climate 2021 (Report). World Meteorological Organization. 2022. p. 2. Archived from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ a b Lindsey, Rebecca; Dahlman, Luann (June 28, 2022). "Climate Change: Global Temperature". climate.gov. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on September 17, 2022.

- ^ Davy, Richard; Esau, Igor; Chernokulsky, Alexander; Outten, Stephen; Zilitinkevich, Sergej (January 2017). "Diurnal asymmetry to the observed global warming". International Journal of Climatology. 37 (1): 79–93. Bibcode:2017IJCli..37...79D. doi:10.1002/joc.4688.

- ^ Schneider, S.H., S. Semenov, A. Patwardhan, I. Burton, C.H.D. Magadza, M. Oppenheimer, A.B. Pittock, A. Rahman, J.B. Smith, A. Suarez and F. Yamin, 2007: Chapter 19: Assessing key vulnerabilities and the risk from climate change. Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, M.L. Parry, O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson, Eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 779-810.

- ^ Joyce, Christopher (30 August 2018). "To Predict Effects Of Global Warming, Scientists Looked Back 20,000 Years". NPR. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ Overpeck, J.T. (20 August 2008), NOAA Paleoclimatology Global Warming – The Story: Proxy Data, NOAA Paleoclimatology Program – NCDC Paleoclimatology Branch, archived from the original on 3 February 2017, retrieved 20 November 2012

- ^ The 20th century was the hottest in nearly 2,000 years, studies show Archived 25 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine, 25 July 2019

- ^ Nicholls, R.J., P.P. Wong, V.R. Burkett, J.O. Codignotto, J.E. Hay, R.F. McLean, S. Ragoonaden and C.D. Woodroffe, 2007: Chapter 6: Coastal systems and low-lying areas. Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, M.L. Parry, O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson, Eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 315-356.

- ^ Oppenheimer, M., B.C. Glavovic , J. Hinkel, R. van de Wal, A.K. Magnan, A. Abd-Elgawad, R. Cai, M. Cifuentes-Jara, R.M. DeConto, T. Ghosh, J. Hay, F. Isla, B. Marzeion, B. Meyssignac, and Z. Sebesvari, 2019: Chapter 4: Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low-Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 321–445. doi:10.1017/9781009157964.006.

- ^ Allen, M.R., O.P. Dube, W. Solecki, F. Aragón-Durand, W. Cramer, S. Humphreys, M. Kainuma, J. Kala, N. Mahowald, Y. Mulugetta, R. Perez, M.Wairiu, and K. Zickfeld, 2018: Chapter 1: Framing and Context. In: Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 49-92. doi:10.1017/9781009157940.003.

- ^ CounterAct; Women's Climate Justice Collective (2020-05-04). "Climate Justice and Feminism Resource Collection". The Commons Social Change Library. Retrieved 2024-07-08.

- ^ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), ed. (2022), "Summary for Policymakers", The Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate: Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 3–36, doi:10.1017/9781009157964.001, ISBN 978-1-009-15796-4, retrieved 2023-04-24

- ^ Doney, Scott C.; Busch, D. Shallin; Cooley, Sarah R.; Kroeker, Kristy J. (2020-10-17). "The Impacts of Ocean Acidification on Marine Ecosystems and Reliant Human Communities". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 45 (1): 83–112. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012320-083019. ISSN 1543-5938. S2CID 225741986.

- ^ EPA (19 January 2017). "Climate Impacts on Ecosystems". Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

Mountain and arctic ecosystems and species are particularly sensitive to climate change... As ocean temperatures warm and the acidity of the ocean increases, bleaching and coral die-offs are likely to become more frequent.

- ^ Pecl, Gretta T.; Araújo, Miguel B.; Bell, Johann D.; Blanchard, Julia; Bonebrake, Timothy C.; Chen, I-Ching; Clark, Timothy D.; Colwell, Robert K.; Danielsen, Finn; Evengård, Birgitta; Falconi, Lorena; Ferrier, Simon; Frusher, Stewart; Garcia, Raquel A.; Griffis, Roger B.; Hobday, Alistair J.; Janion-Scheepers, Charlene; Jarzyna, Marta A.; Jennings, Sarah; Lenoir, Jonathan; Linnetved, Hlif I.; Martin, Victoria Y.; McCormack, Phillipa C.; McDonald, Jan; Mitchell, Nicola J.; Mustonen, Tero; Pandolfi, John M.; Pettorelli, Nathalie; Popova, Ekaterina; Robinson, Sharon A.; Scheffers, Brett R.; Shaw, Justine D.; Sorte, Cascade J. B.; Strugnell, Jan M.; Sunday, Jennifer M.; Tuanmu, Mao-Ning; Vergés, Adriana; Villanueva, Cecilia; Wernberg, Thomas; Wapstra, Erik; Williams, Stephen E. (31 March 2017). "Biodiversity redistribution under climate change: Impacts on ecosystems and human well-being". Science. 355 (6332): eaai9214. doi:10.1126/science.aai9214. hdl:10019.1/120851. PMID 28360268. S2CID 206653576.

- ^ IPCC, 2019: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, E. Calvo Buendia, V. Masson-Delmotte, H.- O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, P. Zhai, R. Slade, S. Connors, R. van Diemen, M. Ferrat, E. Haughey, S. Luz, S. Neogi, M. Pathak, J. Petzold, J. Portugal Pereira, P. Vyas, E. Huntley, K. Kissick, M. Belkacemi, J. Malley, (eds.)]. doi:10.1017/9781009157988.001

- ^ Parmesan, Camille; Morecroft, Mike; Trisurat, Yongyut; et al. "Chapter 2: Terrestrial and Freshwater Ecosystems and their Services" (PDF). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. The Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, Monthly Global Climate Report for Annual 2022, published online January 2023, Retrieved on July 25, 2023 from https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/monthly-report/global/202213.

- ^ Lisiecki, Lorraine E.; Raymo, Maureen E. (January 2005). "A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic d18O records" (PDF). Paleoceanography. 20 (1): PA1003. Bibcode:2005PalOc..20.1003L. doi:10.1029/2004PA001071. hdl:2027.42/149224. S2CID 12788441.

- Supplement: Lisiecki, L. E.; Raymo, M. E. (2005). "Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of globally distributed benthic stable oxygen isotope records". Pangaea. doi:10.1594/PANGAEA.704257.

- ^ Petit, J. R.; Jouzel, J.; Raynaud, D.; Barkov, N. I.; Barnola, J. M.; Basile, I.; Bender, M.; Chappellaz, J.; Davis, J.; Delaygue, G.; Delmotte, M.; Kotlyakov, V. M.; Legrand, M.; Lipenkov, V.; Lorius, C.; Pépin, L.; Ritz, C.; Saltzman, E.; Stievenard, M. (1999). "Climate and Atmospheric History of the Past 420,000 years from the Vostok Ice Core, Antarctica". Nature. 399 (6735): 429–436. Bibcode:1999Natur.399..429P. doi:10.1038/20859. S2CID 204993577.

- ^ Bradley, Raymond S (1999). Paleoclimatology: Reconstructing Climates of the Quaternary. Elsevier. pp. 158–160.

- ^ a b Alley, R. B. (2000-02-15). "Ice-core evidence of abrupt climate changes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 97 (4): 1331–1334. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.1331A. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.4.1331. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 34297. PMID 10677460.

- ^ Severinghaus, Jeffrey P.; Sowers, Todd; Brook, Edward J.; Alley, Richard B.; Bender, Michael L. (January 1998). "Timing of abrupt climate change at the end of the Younger Dryas interval from thermally fractionated gases in polar ice". Nature. 391 (6663): 141–146. Bibcode:1998Natur.391..141S. doi:10.1038/34346. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 4426618.

- ^ Webb, Robert S.; Clark, Peter U.; Keigwin, Lloyd D. (1999), "Preface", Mechanisms of Global Climate Change at Millennial Time Scales, vol. 112, Washington, D. C.: American Geophysical Union, pp. vii–viii, Bibcode:1999GMS...112D...7W, doi:10.1029/gm112p0vii, ISBN 0-87590-095-X, retrieved 2021-04-18

- ^ Chappellaz, Jérôme; Brook, Ed; Blunier, Thomas; Malaizé, Bruno (1997-11-30). "CH4and δ18O of O2records from Antarctic and Greenland ice: A clue for stratigraphic disturbance in the bottom part of the Greenland Ice Core Project and the Greenland Ice Sheet Project 2 ice cores". Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 102 (C12): 26547–26557. Bibcode:1997JGR...10226547C. doi:10.1029/97jc00164. ISSN 0148-0227.

- ^ Higgins, John A.; Kurbatov, Andrei V.; Spaulding, Nicole E.; Brook, Ed; Introne, Douglas S.; Chimiak, Laura M.; Yan, Yuzhen; Mayewski, Paul A.; Bender, Michael L. (2015-05-11). "Atmospheric composition 1 million years ago from blue ice in the Allan Hills, Antarctica". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (22): 6887–6891. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.6887H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1420232112. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4460481. PMID 25964367.

- ^ Brook, Edward J.; Buizert, Christo (June 2018). "Antarctic and global climate history viewed from ice cores". Nature. 558 (7709): 200–208. Bibcode:2018Natur.558..200B. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0172-5. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 29899479. S2CID 49191229.

- ^ Cuffey, Kurt M.; Clow, Gary D.; Steig, Eric J.; Buizert, Christo; Fudge, T. J.; Koutnik, Michelle; Waddington, Edwin D.; Alley, Richard B.; Severinghaus, Jeffrey P. (2016-11-28). "Deglacial temperature history of West Antarctica". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (50): 14249–14254. Bibcode:2016PNAS..11314249C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1609132113. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5167188. PMID 27911783.

- ^ a b Thompson, L. G. (2004), "High Altitude, Mid- and Low-Latitude Ice Core Records: Implications for Our Future", Earth Paleoenvironments: Records Preserved in Mid- and Low-Latitude Glaciers, Developments in Paleoenvironmental Research, vol. 9, Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 3–15, doi:10.1007/1-4020-2146-1_1, ISBN 1-4020-2145-3

- ^ Thompson, L. G.; Mosley-Thompson, E.; Davis, M. E.; Lin, P. -N.; Henderson, K. A.; Cole-Dai, J.; Bolzan, J. F.; Liu, K. -b. (1995-07-07). "Late Glacial Stage and Holocene Tropical Ice Core Records from Huascaran, Peru". Science. 269 (5220): 46–50. Bibcode:1995Sci...269...46T. doi:10.1126/science.269.5220.46. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17787701. S2CID 25940751.

- ^ J.T. Houghton; et al., eds. (2001). "Figure 1: Variations of the Earth's surface temperature over the last 140 years and the last millennium.". Summary for policy makers. IPCC Third Assessment Report - Climate Change 2001 Contribution of Working Group I. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Archived from the original on November 13, 2016. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- ^ J.T. Houghton; et al., eds. (2001). Chapter 2. Observed climate variability and change. Climate Change 2001: Working Group I The Scientific Basis. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- ^ a b c National Research Council (U.S.). Committee on Surface Temperature Reconstructions for the Last 2,000 Years Surface temperature reconstructions for the last 2,000 years (2006), National Academies Press ISBN 978-0-309-10225-4

- ^ Mann, Michael E.; Zhang, Zhihua; Hughes, Malcolm K.; Bradley, Raymond S.; Miller, Sonya K.; Rutherford, Scott; Ni, Fenbiao (2008). "Proxy-based reconstructions of hemispheric and global surface temperature variations over the past two millennia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (36): 13252–13257. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10513252M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805721105. PMC 2527990. PMID 18765811.

- ^ "The Climate Epochs That Weren't". State of the Planet. 2019-07-24. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- ^ O.Muszkat, The outline of the problems and methods used for research of the history of the climate in the Middle Ages, (in polish), Przemyśl 2014, ISSN 1232-7263

- ^ The Fall of the Egyptian Old Kingdom Hassan, Fekri BBC June 2001

- ^ "Mean Monthly Temperature Records Across the Globe / Timeseries of Global Land and Ocean Areas at Record Levels for October from 1951-2023". NCEI.NOAA.gov. National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). November 2023. Archived from the original on 16 November 2023. (change "202310" in URL to see years other than 2023, and months other than 10=October)

- ^ "GCOS - Deutscher Wetterdienst - CLIMAT Availability". gcos.dwd.de. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ "Remote Sensing Systems". www.remss.com. Retrieved 2022-05-19.

- ^ a b IPCC (2021). "Summary for Policymakers" (PDF). The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. ISBN 978-92-9169-158-6.

Recent Comments