American Larch

Larix laricina, commonly known as the tamarack,[3] hackmatack,[3] eastern larch,[3] black larch,[3] red larch,[3] or American larch,[3] is a species of larch native to Canada, from eastern Yukon and Inuvik, Northwest Territories east to Newfoundland, and also south into the upper northeastern United States from Minnesota to Cranesville Swamp, West Virginia; there is also an isolated population in central Alaska.[4]

Description

Larix laricina is a small to medium-size boreal deciduous conifer tree reaching 15–23 m (49–75 ft) tall, with a trunk up to 60 cm (24 in) diameter.[5] The bark of mature trees are reddish, the young trees are gray with smooth bark.[6] The leaves are needle-like, 2.5 cm (1 in) short, light blue-green, turning bright yellow before they fall in the autumn, leaving the shoots bare until the next spring.[5] The needles are produced in clusters on long woody spur shoots.[5] The cones are the smallest of any larch, only 1–2.3 cm (3⁄8–7⁄8 in) long, with 12-25 seed scales; they are bright red, turning brown and opening to release the seeds when mature, 4 to 6 months after pollination.[6]

Key characteristics:[7]

- The needles are normally borne on a short shoot in groups of 10–20 needles.

- The larch is deciduous and the needles turn yellow in autumn.

- The seed cones are small, less than 2 cm (3⁄4 in) long, with lustrous brown scales.

- Larch are commonly found in swamps, fens, bogs, and other low-land areas.

Distribution and ecology

Tamaracks are very cold tolerant, able to survive temperatures down to at least −62 °C (−80 °F), and commonly occurs at the Arctic tree line at the edge of the tundra. Trees in these severe climatic conditions are smaller than farther south, often only 3 m (10 ft) tall. They can tolerate a wide range of soil conditions but grow most commonly in swamps, bogs, or muskegs, in wet to moist organic soils such as sphagnum, peat, and woody peat.[3][6] [5]They are also found on mineral soils that range from heavy clay to coarse sand; thus texture does not seem to be limiting. Although tamarack can grow well on calcareous soils, it is not abundant on the limestone areas of eastern Ontario.[5]

Tamarack is generally the first forest tree to grow on filled-lake bogs.[5][8] In the lake states, tamarack may appear first in the sedge mat, sphagnum moss, or not until the bog shrub stage. Farther north, it is the pioneer tree in the bog shrub stage. Tamarack is fairly well adapted to reproduce successfully on burns, so it is one of the common pioneers on sites in the boreal forest immediately after a fire.[9]

The central Alaskan population, separated from the eastern Yukon populations by a gap of about 700 kilometres (430 mi), is treated as a distinct variety Larix laricina var. alaskensis by some botanists, though others argue that it is not sufficiently distinct to be distinguished.[5]

Damaging agents

Tamaracks are easily susceptible to fires, as they have shallow roots and thin bark.[5] The tamarack's shallow root system also leaves the susceptible to being knocked over by high-speed winds. It has also been discovered that abnormally high water levels often kill tamarack stands.[8] Flooding, mainly caused by beaver dams and newly constructed roads, can kill off stands and damage adventitious roots.[5][8]

Tamaracks are targeted by many species of insects. One of the most prominent damaging insect is larch sawfly, which is non-native.[5][8] They cause damage across their range and cause defoliation which can kill the trees within 6 to 9 years.[5][8] To lessen the problem parasites have been imported to kill the larch sawflies in parts of Minnesota and Manitoba.[8] Another serious defoliator is the larch casebearer (Coleophora laricella). All tamaracks are susceptible to being killed by the larch casebearer, however recently the outbreaks of larch casebearer have been less severe.[8]

There are some other insects that can harm Tamaracks, including spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana), the larch-bud moth (Zeiraphera improbana), the spruce spider mite (Oligonychus ununguis) the larch-shoot moth (Argyresthia laricella), and the eastern larch beetle (Dendroctonus simplex).[8] Healthy trees are left mostly unaffected by eastern larch beetles.[8] Defoliation by the larch casebearer makes infestation of the eastern larch beetle more likely.[10][8]

Only one of the many pathogens that affect Tamarack cause diseases serious enough to have an economic impact on its culture, the Lachnellula willkommii fungus. It is a relatively new pathogen in Canada, first recorded in 1980 and originating in Europe. The fungus cause large cankers to form and a disease known as larch canker which is particularly harmful to the tamarack larch, killing both young and mature trees.[11] Rust is the only common foliage disease amongst Tamaracks, and cause minimal damage to the trees.[8] The needle-cast fungus (Hypodermella laricis) is also cause for concern in Tamaracks.[8]

Associated forest cover

Tamarack forms extensive pure stands in the boreal region of Canada and in northern Minnesota.[5] In the rest of its United States range and in the Maritime Provinces, tamarack is found locally in both pure and mixed stands.[5]

Black spruce (Picea mariana) is usually tamarack's main associate in mixed stands on all sites. Other commonly associated overgrowth species include balsam fir (Abies balsamea), white spruce (Picea glauca), and quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) in the boreal region.[5] In the better organic soil sites in the northern forest region, the most common associates are the northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis), balsam fir, black ash (Fraxinus nigra), and red maple (Acer rubrum).[5] In Alaska, quaking aspen and tamarack are almost never found together.[5] Additional common associates are American elm (Ulmus americana), balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera), jack pine (Pinus banksiana), paper birch (Betula papyrifera), Kenai birch (B. papyrifera var. kenaica), and yellow birch (B. alleghaniensis).[5]

There are a vast number of shrubs associated with Tamarack due to their range, some of the common ones are dwarf and swamp birch (Betula glandulosa and Betula pumila), willows (Salix spp.), speckled alder (Alnus rugosa), and red-osier dogwood (Cornus stolonifera) bog Labrador tea (Ledum groenlandicum), bog-rosemary (Andromeda glaucophylla), leather leaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata), blueberries and huckleberries (Vaccinium spp.) and small cranberry (Vaccinium oxycoccos).[5][8] Characteristically the herbaceous cover includes sedges (Carex spp.), cottongrass (Eriophorum spp.), three-leaved false Solomonseal (Maianthemum trifolium), marsh cinquefoil (Potentilla palustris), marsh-marigold (Caltha palustris), and bogbean (Menyanthes trifoliata).[8]

Uses

The wood is tough and durable, but also flexible in thin strips, and was used by the Algonquian people for making snowshoes and other products where toughness was required. The natural crooks located in the stumps and roots are also preferred for creating knees in wooden boats.[8] Currently, the wood is used principally for pulpwood, but also for posts, poles, rough lumber, and fuelwood; it is not a major commercial timber species.[8] Tamarack wood is also used as kickboards in horse stables.[5] Older log homes built in the 19th century sometimes incorporated tamarack along with other species like red or white oak. The hewn logs have a coarse grainy surface texture.

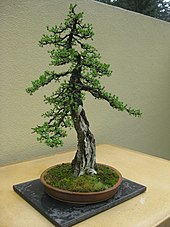

It is also grown as an ornamental tree in gardens in cold regions. Several dwarf cultivars have been created that are available commercially.[12][13] Tamarack is commonly used for bonsai.[14]

Tamarack poles were used in corduroy roads because of their resistance to rot. Tamarack posts were used before 1917 in Alberta to mark the northeast corner of sections surveyed within townships. They were used by the surveyors because at that time the very rot-resistant wood was readily available in the bush and was light to carry.[citation needed] Their rot resistance was also why they were often used in early water distribution systems.

The aboriginal peoples of Canada's northwest regions used the inner bark as a poultice to treat cuts, infected wounds, frostbite, boils and hemorrhoids. The outer bark and roots are also said to have been used with another plant as a treatment for arthritis, cold and general aches and pains.[15]

Wildlife use the tree for food and nesting. Porcupines eat the inner bark, snowshoe hares feeds on tamarack seedlings, and red squirrels eat the seeds.[8] Birds that frequent tamaracks during the summer include the white-throated sparrow, song sparrow, veery, common yellowthroat, and Nashville warbler.[16][8]

Reaction to competition

Tamarack is very intolerant of shade. [8]Although it can tolerate some shade during the first several years, it must become dominant to survive.[8] When mixed with other species, it must be in the over story.[5] The tree is a good self-pruner, and boles of 25- to 30-year-old trees may be clear for one-half or two-thirds their length.[5][8]

Because tamarack is very shade-intolerant, it does not become established in its own shade.[8] Consequently, the more tolerant black spruce eventually succeeds tamarack on poor bog sites, whereas northern white-cedar, balsam fir, and swamp hardwoods succeed tamarack on good swamp sites.[5][8] Recurring sawfly outbreaks throughout the range of tamarack have probably sped the usual succession to black spruce or other associates.[8]

Various tests on planting and natural reproduction indicate that competing vegetation hinders tamarack establishment.[8]

The shade-intolerance of tamarack dictates the use of even-aged management.[5][8] Some adaptation of clear cutting or seed-tree cutting is generally considered the best silvicultural system because tamarack seeds apparently germinate better in the open, and the seedlings require practically full light to survive and grow well.[8] Tamarack is also usually wind-firm enough for the seed-tree system to succeed. Satisfactory reestablishment of tamarack, however, often requires some kind of site preparation, such as slash disposal and herbicide spraying.[8]

Names

The names tamarack and hackmatack appear to derive from Algonquian but have undergone contamination with the word tacamahac, from Nahuatl, so the precise words that underlie them are unclear.[17] The word akemantak meaning "wood used for snowshoes" has been cited[by whom?] as a name for the species, but the Proto-Algonquian *a·kema·xkwa this appears to represent was the name for the white ash.[18]

Gallery

-

Young female cone

-

Old seed cones

See also

References

- ^ Farjon, A. (2013). "Larix laricina". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T42313A2971618. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T42313A2971618.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Larix laricina". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew – via The Plant List. Note that this website has been superseded by World Flora Online

- ^ a b c d e f g Earle, Christopher J., ed. (2018). "Larix laricina". The Gymnosperm Database. Retrieved 2011-05-28.

- ^ "Larix laricina". State-level distribution map from the North American Plant Atlas (NAPA). Biota of North America Program (BONAP). 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Uchytil, Ronald J. (1991). "Larix laricina". Fire Effects Information System (FEIS). US Department of Agriculture (USDA), Forest Service (USFS), Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory.

- ^ a b c Parker, William H. (1993). "Larix laricina". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 2. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- ^ Barnes, Burton V.; Wagner Jr., Warren H. (September 15, 1981). Michigan Trees. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08018-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Johnston, William F. (1990). "Larix laricina". In Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H. (eds.). Conifers. Silvics of North America. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: United States Forest Service (USFS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 2015-12-04 – via Southern Research Station.

- ^ Hogan, C. Michael (November 24, 2008). "Black Spruce". GlobalTwitcher.com. Archived from the original on October 5, 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-28.

- ^ McKee, Fraser (2015). "1.2 Factors associated with the increased tree-killing activity of eastern larch beetles". Biology and population dynamics of the eastern larch beetle, Dendroctonus simplex LeConte, and its interactions with eastern larch (tamarack), Larix laricina (PhD). University of Minnesota.

- ^ European larch canker Natural Resources Canada

- ^ "Larix laricina". University of Connecticut. Archived from the original on 2013-03-15. Retrieved 2012-11-15.

Dwarf forms include: 'Blue Sparkler', with bluish foliage; 'Deborah Waxman', which reaches 4' in time; 'Lanark', which grows very low and wide; and 'Newport Beauty', a tiny form probably never exceeding 2' tall and wide.

- ^ "Larix Laricina: Cultivar List". Encyclopedia of Conifers. Royal Horticultural Society.

- ^ Joyce, David (2006). The Art of Natural Bonsai: Replicating Nature's Beauty. Sterling Publishing Company. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-4027-3524-0.

As bonsai, they are my favorite genus because of their speed of growth, hardiness, ease of wiring and shaping, and, most of all, for their beautiful foliage color in spring and autumn.

- ^ Marles, Robin James (2009). Aboriginal Plant Use in Canada's Northwest Boreal Forest. Canadian Forest Service. ISBN 978-0-660-19869-9.

- ^ Dawson, Deanna K. 1979. Bird communities associated with succession and management of lowland conifer forests. In Management of north central and northeastern forests for nongame birds: workshop proceedings, 1979. p. 120-131. USDA Forest Service, General Technical Report NC-51. North Central Forest Experiment Station, St. Paul, MN.

- ^ "hackmatack, n., Etymology". Oxford English Dictionary. July 2023. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

- ^ Siebert, Frank T. (1967). "The original home of the Proto-Algonquian people". Algonquian Papers-Archive. 1. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

External links

- Larix laricina images at the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University Plant Image Database

- Enzenbacher, Tiffany. "Plant Collecting in the Wisconsin Wilds". Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University website, 30 August 2017. Accessed 12 May 2020.

- Earl J. S. Rook, Boundary Waters Compendium, Flora, Fauna, Earth, and Sky, The Natural History of the Northwoods, Trees of the Northwoods, Larix laricina

Recent Comments