White Southerners (historically referred to as Southrons)[4] are a regional culture[5][6] and identity[7][8][9] of White Americans from the Southern United States, primarily originating from the various waves of Northwestern and Southern European immigration to the region beginning in the 16th century to the British Southern colonies, French Louisiana[10], the Spanish-American colonies; and the subsequent waves of immigration from other parts of Europe[11][12][13][14], the Caribbean[15], Latin America[16][17], and the Mediterranean.[18][19] Though overwhelmingly of European descent, many blacks in the South assimilated into the white population, resulting in about 10% of white Southerners having traceable African ancestry per some studies.[20][21]

Historical identity

The first Europeans

Evidence of Europeans in the American South can definitively be traced back to 1513 when Spaniard conquistador, Juan Ponce de León, disembarked in Florida.[22] Though despite being the earliest Europeans in what would later become the Southern United States, the Spanish were unable to establish permanent settlements beyond Florida and Texas due to Native American raids and conflict with the English.

Due to this, the majority of white Southern culture, language, religion, traditions, and folkways can be traced back to the waves of immigrants arriving from the British Isles in the 17th-18th centuries.[23][24][25]

Early cultural observations

In 1765, London philanthropist Dr. John Fothergill remarked on the cultural differences of the British American colonies southward from Maryland and those to the north, suggesting that the Southerners were marked by "idleness and extravagance". Fothergill suggested that Southerners were more similar to the people of the Caribbean than to the colonies to the north.[26] Early in United States history, the contrasting characteristics of Southern states were acknowledged in a discussion between Thomas Jefferson and François-Jean de Chastellux. Jefferson ascribed the Southerners' "unsteady", "generous", "candid" traits to their climate, while De Chastellux claimed that Southerners' "indelible character which every nation acquires at the moment of its origin" would "always be aristocratic" not only because of slavery but also "vanity and sloth". A visiting French dignitary concurred in 1810 that American customs seemed "entirely changed" over the Potomac River, and that Southern society resembled those of the Caribbean.[26]

Northern popular press and literature in this early period of US history often used a "we"-versus-"they" dichotomy when discussing Southerners, and looked upon Southern customs as backward and a threat to progress. For instance, a 1791 article in the New York Magazine warned that the spread of Southern cockfighting was tantamount to being "assaulted" by "the enemy within" and would "rob" the nation's "honor". J. Hector St. John de Crèvecœur's 1782 Letters from an American Farmer declared that although slavery had not been completely abolished in the Northern states, conditions in Southern slavery was "different... in every respect", emphasizing the contrasting treatment of slaves. Crèvecœur sought to portray Southerners as stuck in the social, cultural and economic remnants of colonialism, in contrast to the Northerners whom he considered to be representative of the distinctive culture of the new nation.[32]

Development of Anglo-American nationalism in the Southern states

The War of 1812 brought increasing awareness to the differences between Northerners and Southerners, who had opposed and supported the war respectively. The Panic of 1819 and the 1820 admission of Missouri as a slave state also exacerbated the North–South divide. In 1823, New York activist Gerrit Smith commented that there was an almost "national difference of character between the people of the Northern and the people of the Southern states." Similarly, a 1822 commentary in the North American Review suggested that Southerners were "a different race of men", "highminded and vainglorious" people who lived on the plantations.[37]

Some Southern writers in the lead up to the American Civil War (1861–1865) built on the idea of a Southern nation by claiming that secession was not based on slavery but rather on "two separate nations". These writers postulated that Southerners were descended from Norman cavaliers, Huguenots, Jacobites and other supposed "Mediterranean races" linked to the Romans, while Northerners were claimed to be descended from Anglo-Saxon serfs and other Germanic immigrants who had a supposed "hereditary hatred" against the Southerners.[38] The white planter class was believed to subscribe to a code of Southern chivalry,[39] descended from that of the Virginia Cavaliers.[40] These ethnonationalist beliefs of being a "warrior race" widely disseminated among the Southern upper class, and Southerners began to use the term "Yankee" as a slur against a so-called "Yankee race" that they associated with being "calculating, money worshipping, cowardly" or even as "hordes" and "semi-barbarian".[41] Southern ideologues also used their alleged Norman ancestors to explain their attachment to the institution of slavery, as opposed to the Northerners who were denigrated as descendants of a so-called "slave race".[41] Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and German-American political scientist Francis Lieber, who condemned the Southerners' belief in their supposed distinct ancestry, attributed the Civil War's outbreak to that belief. In 1866, Edward A. Pollard, author of the first history book on the Confederacy The Lost Cause, continued insisting that the South had to "assert its well-known superiority in civilization over the people of the North."[41] Southerners developed their ideas on nationalism on influences from the nationalist movements growing in Europe (such as the works of Johann Gottfried Herder and the constructed north–south divide between Germanic peoples and Italians). Southern ideologues, fearful of mass politics, sought to adopt the ethnic themes of the revolutions of 1848 while distancing themselves from the revolutionaries' radical liberal ideas.[42] The slaveholding elite encouraged Romantic "antimodern" narratives of Southern culture as a refuge of traditional community hospitality and chivalry to mobilize popular support from non-slaveholding White Southerners, promising to bring the South through a form of technological and economic progress without the perceived social ills of modern industrial societies.[42]

Military tradition

White Southerners have always composed a significant percentage of the United States military and have historically contributed many military leaders.[43][44]

Various factors contribute to this martial tradition including; socio-economic factors, the high presence of military bases in the region, and most importantly, the culture of chivalry. Researchers have compared the Southern military tradition to other traditionally martial cultures, such as the Prussian Junkers.[45][46]

This military tradition was a major advantage the Confederate States of America had over the United States during the American Civil War, as white Southerners had dominated the United States military prior to 1860.[47]

Influence of African-Americans and Native Americans

There is a long history of mixing between both white and black Southerners; socially, racially, and culturally. Both groups have existed in the South since the 17th century and thus share many cultural traits. For example, some researchers believe AAVE evolved out of the dialects of poor English indentured servants who worked the fields alongside African slaves and servants.[48] In addition, many white-led abolitionist groups in the decades leading up to the American Civil War were located in the Southern states,[49][50][51] free blacks shaped the Southern backcountry alongside their white neighbors, the majority of music traditions[52][53] and cuisine[54] originating in the Southern US are of Afro-European origin, and the South has a long history of racially integrated labor movements.[55]

The Civil War to the New South

Until the ratification of the 13th Amendment on December 6, 1865, African chattel slavery formed a crucial role in the development of white Southern cultural consciousness and was the primary cause of the formation of the Confederate States of America.[58] In the eleven-thirteen states that seceded from the United States in 1860–61 to form the Confederacy, 31% of families held at least one African American in slavery.[59] On March 21, 1861, Confederate vice president Alexander Stephens gave his infamous Cornerstone Speech in which he stated the following:

"The constitution, it is true, secured every essential guarantee to the institution while it should last, and hence no argument can be justly urged against the constitutional guarantees thus secured, because of the common sentiment of the day. Those ideas, however, were fundamentally wrong. They rested upon the assumption of the equality of races. This was an error. It was a sandy foundation, and the government built upon it fell when the "storm came and the wind blew." Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth."[60]

During the Reconstruction era, white Southern paramilitaries such as the Ku Klux Klan, Redeemers, White League, and Red Shirts, waged a guerilla war on Federal forces and newly emancipated blacks in order to reestablish Southern Democrat control.[61][62] President Rutherford B. Hayes would go on to withdraw the last Federal troops from the South in 1877,[63] allowing for these white supremacist politicians and militias to retake control. Upon regaining power, white Southerners would once again disenfranchise and terrorize black Southerners, ushering in the Jim Crow era. Only in 1964 did the Civil Rights Act legally end Jim Crow laws which mandated the segregation of races in the Southern United States.[64][65][66] Upon white Southerners Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton being elected to the U.S. presidency during the late 20th century, it symbolized generations of change from an Old South to New South society. Journalist Hodding Carter and State Department spokesperson during the Carter Administration stated: "The thing about the South is that it's finally multiple rather than singular in almost every respect." The transition from President Carter to President Clinton also mirrored the social and economic evolution of the South in the mid-to-late 20th century.[67]

Academic research

Sociologist William L. Smith argues that "regional identity and ethnic identity are often intertwined in a variety of interesting ways such that some scholars have viewed white southerners as an ethnic group".[68] In her book Southern Women, Caroline Matheny Dillman also documents a number of authors who posit that Southerners might constitute an ethnic group. She notes that the historian George Brown Tindall analyzed the persistence of the distinctiveness of Southern culture in The Ethnic Southerners (1976), "and referred to the South as a subculture, pointing out its ethnic and regional identity". The 1977 book The Ethnic Imperative, by Howard F. Stein and Robert F. Hill, "viewed Southerners as a special kind of white ethnicity". Dillman notes that these authors, and earlier work by John Shelton Reed, all refer to the earlier work of Lewis Killian, whose White Southerners, first published in 1970, introduced "the idea that Southerners can be viewed as an American ethnic group".[69] Killian does however note, that: "Whatever claims to ethnicity or minority status ardent 'Southernists' may have advanced, white southerners are not counted as such in official enumerations".[70]

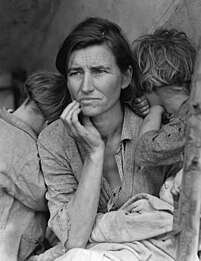

Precursors to Killian include sociologist Erdman Beynon, who in 1938 made the observation that "there appears to be an emergent group consciousness among the southern white laborers", and economist Stuart Jamieson, who argued four years later in 1942 that Oklahomans, Arkansans and Texans who were living in the valleys of California were starting to take on the "appearance of a distinct 'ethnic group'". Beynon saw this group consciousness as deriving partly from the tendency of northerners to consider them as a homogeneous group, and Jamieson saw it as a response to the label "Okie".[71] More recently, historian Clyde N. Wilson has argued that "In the North and West, white Southerners were treated as and understood themselves to be a distinct ethnic group, referred to negatively as 'hillbillies' and 'Okies'".[72]

The Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, published in 1980, includes a chapter on Southerners authored by John Shelton Reed, alongside chapters by other contributors on Appalachians and Yankees. Writing in the journal Ethnic and Racial Studies, social anthropologist M. G. Smith argued that the entries do not satisfactorily indicate how these groups meet the criteria of ethnicity, and so justify inclusion in the encyclopedia.[73] Historian David L. Carlton, argues that Killian, Reed and Tindall's "ethnic approach does provide a way to understand the South as part of a vast, patchwork America, the components of which have been loath to allow their particularities to be eaten away by the corrosions of a liberal-capitalist order", nonetheless notes problems with the approach. He argues that the South is home to two ethnic communities (white and black) as well as smaller, growing ethnic groups, not just one. He argues that: "Most important, though, and most troubling, is the peculiar relationship of white southerners to the nation's history." The view of the average white Southerner, Carlton argues, is that they are quintessential Americans, and their nationalism equates "America" with the South.[74]

White Southern diaspora

Okies and Arkies

Poor white and Native American migrant farmers from Oklahoma and Arkansas made the trek from their home states to the Central Valley of California during the Dust Bowl, which ecologically devastated the region. These migrants would synthesize into a unique cultural group in California, creating the Bakersfield sound country music genre, the rural inland dialect of California English, and inspiring John Steinbeck's award-winning novel, The Grapes of Wrath.[75][76][77]

Confederados

The Confederados of Brazil are the descendants of some 20,000 post-Civil War Southern immigrants who left the United States due to their opposition to abolition and Reconstruction. They introduced Southern cuisine, the Southern Baptist Church, American educational methods, and improved methods of cotton farming.[78][79]

"Many persons who, from long habit and fondly cherished theories, have become strongly attached to the institution of African slavery, fancy that in Brazil they will find an opportunity for the permanent use of that system of labor — Brazil and the Spanish possessions being the only two slaveholding communities remaining in the civilized world," - New Orleans Daily Picayune, September 1865.[80]

Confederate Belizeans

Descendants of Confederate immigrants form a distinct sub-group in Belize. Their ancestors had left the United States due to Reconstruction and the abolition of slavery. Well known Confederate Belizeans include Confederate politician Colin J. McRae and Joseph Benjamin, brother of Confederate Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin.[81][82]

See also

- Mountain white

- Poor White, a sociocultural group

- Black Southerners

- Redneck

- Hillbilly

- History of the Southern United States

- White Americans in Texas

- Jews in the Southern United States

- Cajuns

- Cracker (term)

- French Louisianians

- Country (identity)

- White Americans in Louisiana

- White Americans in Maryland

- History of Italians in Arkansas

- History of Italians in Mississippi

- Floridanos

- White trash

References

- ^ "Race and Ethnicity in the South (Region)".

- ^ "Religious Landscape Study".

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Religion in the South".

- ^ Hendrickson, Robert (2000-10-30). The Facts on File Dictionary of American Regionalisms. Infobase Publishing. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-4381-2992-1.

- ^ Jones, Suzanne W.; Monteith, Sharon (2002-11-01). South to A New Place: Region, Literature, Culture. LSU Press. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-0-8071-2840-4.

- ^ Maxwell, Angie (2014-04-15). The Indicted South: Public Criticism, Southern Inferiority, and the Politics of Whiteness. UNC Press Books. pp. 254, 297. ISBN 978-1-4696-1165-5.

- ^ Dickson, Keith D. (2011-11-21). Sustaining Southern Identity: Douglas Southall Freeman and Memory in the Modern South. LSU Press. pp. 3–5, 242. ISBN 978-0-8071-4005-5.

- ^ Quigley, Paul (2011-11-24). Shifting Grounds: Nationalism and the American South, 1848-1865. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-19-973548-8.

- ^ Feldman, Glenn (2019-10-01). Nation within a Nation: The American South and the Federal Government. University Press of Florida. pp. Ch. 7, 1–2. ISBN 978-0-8130-6529-8.

- ^ Hirsch, Arnold R.; Logsdon, Joseph (1992-09-01). Creole New Orleans: Race and Americanization. LSU Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-8071-1774-3.

- ^ Gleeson, David T. (2002-11-25). The Irish in the South, 1815-1877. Univ of North Carolina Press. pp. 1–4. ISBN 978-0-8078-7563-6.

- ^ "Ungesund: Yellow Fever, the Antebellum Gulf South, and German Immigration". Southern Spaces. Retrieved 2024-05-27.

- ^ Baker, T. Lindsay (1996). The First Polish Americans: Silesian Settlements in Texas. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 1–6. ISBN 978-0-89096-725-6.

- ^ Jackson, Jessica Barbata (2020-04-15). Dixie’s Italians: Sicilians, Race, and Citizenship in the Jim Crow Gulf South. LSU Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-7375-6.

- ^ Gershon, Livia (21 January 2024). "How Jim Crow Divided Florida's Cubans". JSTOR Daily.

- ^ Havard, John C. (2018-04-10). Hispanicism and Early US Literature: Spain, Mexico, Cuba, and the Origins of US National Identity. University of Alabama Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-8173-1977-9.

- ^ "One Mexicans as Europeans: Mexican Nationalism and Assimilation in New Orleans, 1910–1939". academic.oup.com. Retrieved 2024-06-17.

- ^ Gualtieri, Sarah (2009-05-06). Between Arab and White: Race and Ethnicity in the Early Syrian American Diaspora. University of California Press. pp. 54–56. ISBN 978-0-520-94346-9.

- ^ Walton, Shana; Carpenter, Barbara (2012-04-02). Ethnic Heritage in Mississippi: The Twentieth Century. Univ. Press of Mississippi. pp. 189–195. ISBN 978-1-61703-263-9.

- ^ Christopher Ingraham (December 22, 2014). "A lot of Southern whites are a little bit black". Washington Post.

- ^ Katarzyna Bryc; Eric Y. Durand; J. Michael Macpherson; David Reich; Joanna L. Mountain (December 18, 2014). "The Genetic Ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 96 (1): 37–53. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.11.010. PMC 4289685. PMID 25529636.

- ^ "Trying to understand white Southerners | Arkansas Democrat Gazette". www.arkansasonline.com. 2023-03-26. Retrieved 2024-06-04.

- ^ Southern Culture: An Introduction, Third Edition (9781611631043). Authors: John Beck, Wendy Jean Frandsen, Aaron Randall. Carolina Academic Press. pp. xvi.

- ^ Gleeson, David T. (2001). The Irish in the South, 1815-1877. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4968-2.[page needed]

- ^ Bozeman, Summer (2018-02-27). "Dive Into Savannah's Irish History | Visit Savannah". visitsavannah.com. Retrieved 2024-05-27.

- ^ a b James C. Cobb (2005). Away Down South A History of Southern Identity. Oxford University Press. pp. 10–12. ISBN 978-0-19-802501-6.

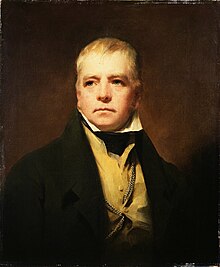

- ^ Horton, Scott (29 July 2007). "How Walter Scott Started the American Civil War: Sidney Blumenthal on the origins of the Republican Party, the fallout from Clinton's emails, and his new biography of Abraham Lincoln". Harper's Magazine.

- ^ "The Great-Granddaddy of White Nationalism". Southern Cultures. 2019-09-26. Retrieved 2024-05-27.

- ^ Wachtell, Cynthia (6 July 2012). "The Author of the Civil War". Opinionator.

- ^ "From: Life on the Mississippi". twain.lib.virginia.edu. Retrieved 2024-05-27.

- ^ Bainbridge, Simon (2003). "Epilogue: The 'Sir Walter Disease' and the Legacy of Romantic War". British Poetry and the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. pp. 225–227. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198187585.003.0008. ISBN 978-0-19-818758-5.

- ^ James C. Cobb (2005). Away Down South A History of Southern Identity. Oxford University Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-0-19-802501-6.

- ^ Paskoff, Paul F.; Wilson, Daniel J. (1982). The Cause of the South: Selections from De Bow's Review, 1846-1867. LSU Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-1039-3.[page needed]

- ^ Miles, Edwin A. (1971). "The Old South and the Classical World". The North Carolina Historical Review. 48 (3): 258–275. JSTOR 23518350.

- ^ Moore, J. Quitman. "Southern Civilization; or, The Norman in America". De Bow's Review. 32 (1–2): 1–19.

- ^ Hanlon, Christopher (2013-01-24). "Puritans vs. Cavaliers". Opinionator. Retrieved 2024-05-27.

- ^ Cobb, James C. (2005). Away Down South A History of Southern Identity. Oxford University Press. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-19-802501-6.

- ^ De Bow's Review Volume 30 Issues 1–4. J.D.B. De Bow. 29 August 1861. pp. 48, 162, 261.

- ^ Genovese, Eugene D. (2000). "The Chivalric Tradition in the Old South". The Sewanee Review. 108 (2): 188–205. JSTOR 27548832.

- ^ Michie, Ian. "The Virginia Cavalier", Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 12 May 2024

- ^ a b c McPherson, James M. (2014). "'Two irreconcilable peoples'? Ethnic Nationalism in the Confederacy". In Lewis, Simon; Gleeson, David T. (eds.). The Civil War as Global Conflict: Transnational Meanings of the American Civil War. University of South Carolina Press. pp. 85–97. ISBN 978-1-61117-326-0. Project MUSE chapter 1122822.

- ^ a b Doyle, Don H. (2010). "The Origins of the Antimodern South: Romantic Nationalism and the Secession Movement in the American South". Secession as an International Phenomenon: From America?s Civil War to Contemporary Separatist Movements. University of Georgia Press. pp. 174–190. ISBN 978-0-8203-3737-1. Project MUSE chapter 328000.

- ^ Kane, Tim. "Who Bears the Burden? Demographic Characteristics of U.S. Military Recruits Before and After 9/11". The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 2020-09-15.

- ^ Wood, Louise, Amy (2010). The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Volume 19: Violence. Univ of North Carolina Press, sponsored by the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi and the Center for the Study of the American South. pp. 112–115. ISBN 9780807869284.

- ^ Bonner, James C. (1955). "The Historical Basis of Southern Military Tradition". The Georgia Review. 9 (1): 74–85. ISSN 0016-8386.

- ^ Maley, Adam; Hawkins, Daniel (2018-01-01). "The Southern Military Tradition: Sociodemographic Factors, Cultural Legacy, and United States Army Enlistments". Armed Forces & Society. 44: 195–218.

- ^ "American Civil War - Secession, Battles, Armies | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2024-06-10. Retrieved 2024-06-15.

- ^ "A Brief History of AAVE". The Garfield Messenger. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

- ^ "Vol. 27, No. 3: The Abolitionist South". Southern Cultures. 2021-11-03. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

- ^ "Brag Bowling: How pervasive was the abolitionist movement and did it influence any of the southern states to secede?". Washington Post. 2024-05-13. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

- ^ "Anti-Slavery Movement in the United States". National Library of Australia. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

- ^ Gatlinburg, Mailing Address: 107 Park Headquarters Road; Us, TN 37738 Phone:436-1200 Contact. "African American Southern Appalachian Music - Great Smoky Mountains National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "A Dive into the Black History of Country Music: Giving Credit Where it's Due". The Skidmore News. 2022-02-23. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

- ^ Arellano, Gustavo (2018-07-26). "How Southern Food Has Finally Embraced Its Multicultural Soul". TIME. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Arkansas". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

- ^ Moyer, Justin Wm (2021-10-25). "The Confederacy's pathetic case of flag envy". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2024-06-11.

- ^ "Cornerstone Contributions: Calling Cards—An Introduction From the Past". DHR. 2022-03-02. Retrieved 2024-06-11.

- ^ Springfield, Mailing Address: 413 S. 8th Street; Us, IL 62701 Phone: 217 492-4241 Contact. "Slavery as a Cause of the Civil War - Lincoln Home National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2024-05-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Bonekemper, Edward H. (2015). The Myth of the Lost Cause: Why the South Fought the Civil War and Why the North Won. Simon and Schuster. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-62157-473-6.

- ^ "Cornerstone Speech". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved 2024-05-30.

- ^ "Reconstruction vs. Redemption". The National Endowment for the Humanities. Retrieved 2024-05-30.

- ^ "NCpedia | NCpedia". www.ncpedia.org. Retrieved 2024-05-30.

- ^ MADEO. "Apr. 24, 1877 | Hayes Withdraws Federal Troops from South, Ending Reconstruction". calendar.eji.org. Retrieved 2024-05-30.

- ^ "Historical Foundations of Race". National Museum of African American History and Culture. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

- ^ "RACE - The Power of an Illusion . Background Readings | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

- ^ "Black History Milestones: Timeline". HISTORY. 2024-01-24. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

- ^ Applebome, Peter (10 November 1992). "From Carter to Clinton, A South in Transition". New York Times. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Smith, William L. (2009). "Southerner and Irish? Regional and Ethnic Consciousness in Savannah, Georgia". Southern Rural Sociology. 24 (1): 223–239.

- ^ Dillman, Caroline Matheny (1988). "The Sparsity of Research and Publications on Southern Women: Definitional Complexities, Methodological Problems, and Other Impediments". In Dillman, Caroline Matheny (ed.). Southern Women. New York: Routledge. p. 6. ISBN 0-89116-838-9.

- ^ Killian, Lewis M. (1985). White Southerners (revised ed.). Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0870234880.

White Southerners Killian.

- ^ Gregory, James N. (2005). The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 166–167. ISBN 978-0807829837.

- ^ Wilson, Clyde (13 August 2014). "What is a Southerner?". Abbeville Institute. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ Smith, M. G. (1982). "Ethnicity and ethnic groups in America: the view from Harvard" (PDF). Ethnic and Racial Studies. 5 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1080/01419870.1982.9993357. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-07-21. Retrieved 2015-06-24.

- ^ Carlton, David L. (1995). "How American is the American South?". In Griffin, Larry J.; Doyle, Don H. (eds.). The South as an American Problem. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-0-8203-1752-6.

- ^ "Okie Migrations | The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture". Oklahoma Historical Society | OHS. Retrieved 2024-06-02.

- ^ "The Bakersfield Sound - Buck Owens, Merle Haggard, The Crystal Palace, Trouts and more!". Visit Bakersfield. Retrieved 2024-06-02.

- ^ "Column: 'Okie' was a California slur for white people. Why it still packs such an ugly punch". Los Angeles Times. 2022-09-21. Retrieved 2024-06-02.

- ^ "Folha de S.Paulo - SP abriga sulista que o vento levou - 16/03/98". www1.folha.uol.com.br. Retrieved 2024-06-02.

- ^ Romero, Simon (2016-05-08). "A Slice of the Confederacy in the Interior of Brazil". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-06-02.

- ^ "Confederados". The Times-Picayune. 1865-09-14. p. 2. Retrieved 2024-06-02.

- ^ "College of Liberal Arts - The College Letter". 2013-07-19. Archived from the original on 2013-07-19. Retrieved 2024-06-02.

- ^ mnoble. "The American Confederates". Belize Info Center. Retrieved 2024-06-02.

Further reading

- Griffin, Larry J.; Evenson, Ranae Jo; Thompson, Ashley B. (2005). "Southerners, All?". Southern Cultures. 11 (1): 6–25. doi:10.1353/scu.2005.0005. S2CID 201776159.

- Lind, Michael (5 February 2013). "The white South's last defeat". Salon. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- Moltke-Hansen, David (2003). "The Rise of Southern Ethnicity". Historically Speaking. 4 (5): 36–38. doi:10.1353/hsp.2003.0034. S2CID 161847511.

- Reed, John Shelton (1980). "Southerners". In Thernstrom, Stephan; Orlov, Ann; Handlin, Oscar (eds.). Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University. pp. 944–948. ISBN 0674375122. OCLC 1038430174.

- Tindall, George B. (1974). "Beyond the Mainstream: The Ethnic Southerners". The Journal of Southern History. 40 (1): 3–18. doi:10.2307/2206054. JSTOR 2206054.

Recent Comments